Healers, Grifters, and Gunslingers: A Visitor's Guide to Surviving 19th-Century Hot Springs

Before the gangsters, a trip to America's first health resort was a gauntlet of highwaymen, con artists, and warring lawmen. Welcome to the real Wild West.

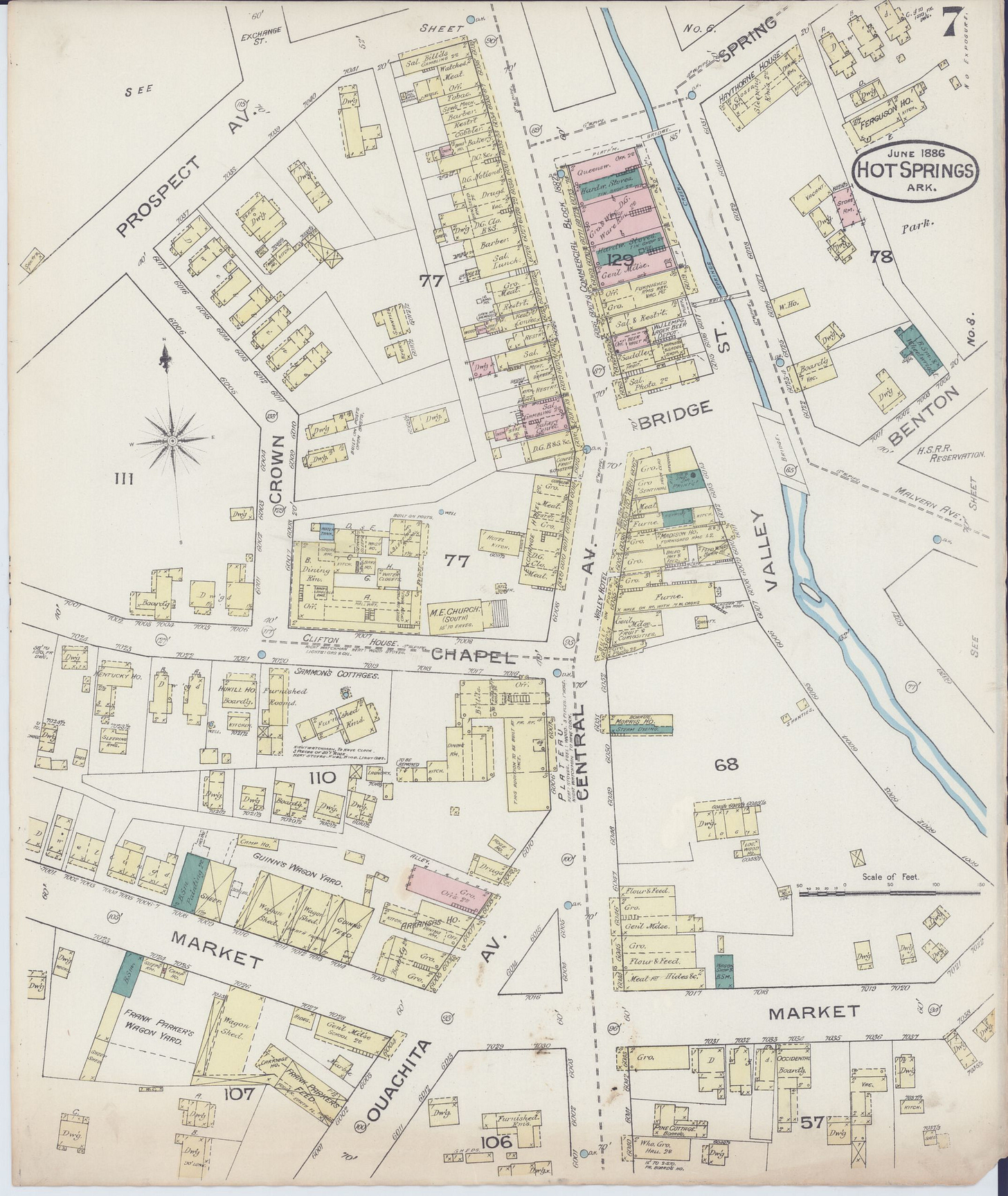

If you flip through the official brochures of American history, Hot Springs, Arkansas, gets a pretty respectable entry. In 1832, long before anyone had even imagined a national park, President Andrew Jackson himself signed the legislation that set aside the valley and its miraculous thermal waters as the nation’s first federal reservation. It was meant to be a sanctuary, a place consecrated to healing where the sick and suffering could find relief. It was, for all intents and purposes, “America’s First Resort.”

But here’s the thing about old brochures: they leave out the really juicy parts. For most of the 19th century, arriving in Hot Springs wasn’t the end of a perilous journey; it was the beginning of one. A trip to the celebrated spa was a calculated risk that demanded a sharp eye and a hand never far from your wallet - or your pistol.

Forget the sanitized tales of Gilded Age relaxation. The raw truth is that 19th-century Hot Springs was a frontier boomtown seething with every stripe of opportunist imaginable. To get here, you had to run a gauntlet of threats that would make a modern traveler’s blood run cold. First, you had to survive the trail, a favorite hunting ground for notorious highwaymen like the James-Younger Gang, who knew that visitors came carrying cash. If you made it to the city limits with your valuables intact, you were then met by a sophisticated ecosystem of urban predators: “doctor drummers” who preyed on the sick, and charming con men who worked hand-in-glove with corrupt authorities to fleece you of your savings.

And the authorities? They were arguably the most dangerous threat of all. Long before Al Capone and Owney Madden made Hot Springs their playground, the city’s power structure was defined by a culture of violence so profound that it culminated in the city’s own lawmen gunning each other down in the street over control of the gambling rackets. So, strap in. This is the story of that other Hot Springs - the one built on a bedrock of desperation, grift, and gunsmoke. Welcome to the real Wild West!

The Perilous Pilgrimage

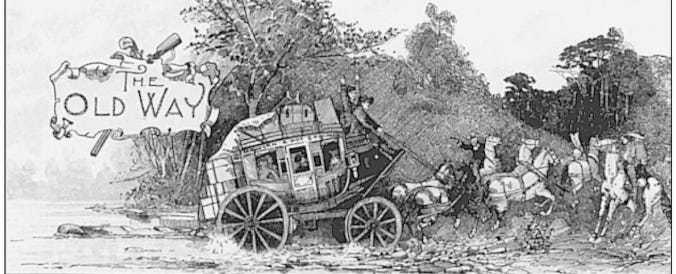

Today, we complain if the WiFi on the interstate gets a little spotty. But for the 19th-century traveler, particularly before 1875, the journey to Hot Springs was a brutal test of fortitude. The final leg of the trip began at the railroad depot in Malvern, where hopeful visitors boarded a stagecoach for a punishing 21-mile trek over what could only generously be called a road. It was a body-jarring ride that could take the better part of a day, winding through dense forests and over steep mountains. Overturns and breakdowns were common, and passengers were often expected to get out and walk up steep hills - or in some cases, even help push the overloaded stagecoach to the crest. For the scores of invalids who made up a considerable portion of the travelers, this torturous journey was an agonizing prelude to their supposed cure.

But the physical ordeal was only half the battle. The real terror of the trail was the constant threat of highway robbery. The wilderness of the Ouachitas, which gave the spa its beauty, also made it a perfect hunting ground for outlaws who knew that visitors heading to a resort would be carrying large sums of cash and valuables. This danger was made terrifyingly real on the cold morning of January 15, 1874.

Five miles outside of Hot Springs, as the stagecoach rattled toward Gulpha Creek, it was brought to a sudden halt by a group of five heavily armed men in long blue coats, their faces partially hidden. The bandits, widely believed to be the infamous James-Younger Gang, were ruthlessly efficient. They ordered all passengers out of the coach and the accompanying hack ambulance and systematically plundered their captives. Among the victims was a former governor of the Dakota Territory, who was relieved of $840 in cash, a gold watch, and a diamond stick pin. The haul from all the passengers was estimated to be over $ 4,000 in cash and jewelry.

The event became a legendary example of the gang’s complex “gentleman bandit” mythos. According to witnesses, when one passenger declared himself a Confederate veteran, the robbers questioned him about his service and, satisfied with the answers, returned all his stolen property. Their chivalry, however, didn’t extend to a traveler from Massachusetts, whose Northern accent reportedly infuriated them so much that they terrorized him by shooting near his body for sport. After seizing the mail sacks, the outlaws vanished back into the wooded hills. A posse was formed, but they were never caught. For those arriving in the valley, the message was clear: the path to America’s great health spa ran straight through the heart of the lawless West.

Predators at the Station

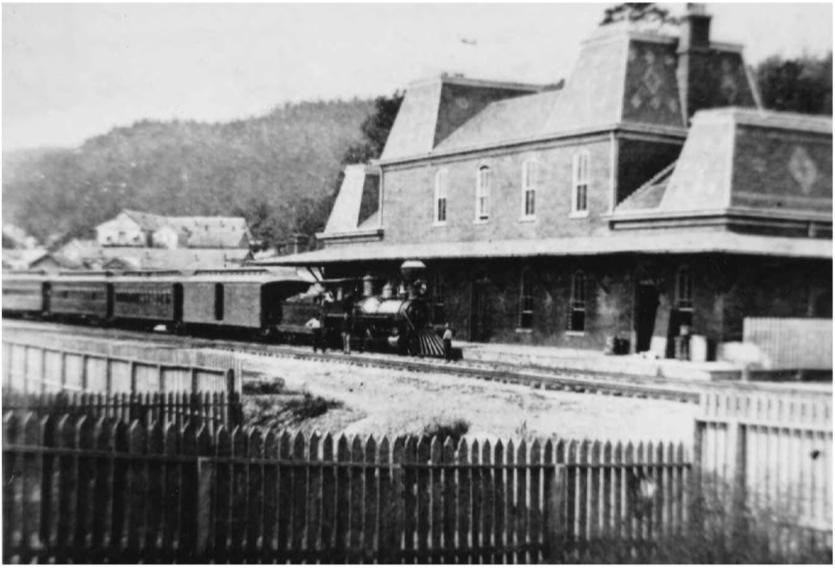

The arrival of Joseph “Diamond Joe” Reynolds’s narrow-gauge railroad in 1875 was supposed to be a game-changer. It transformed the brutal, day-long stagecoach ordeal into a comfortable one-hour trip in beautifully appointed cars with rosewood interiors and velvet draperies. For the first time, Hot Springs was easily accessible, and the resulting flood of money and visitors fueled the rise of grand hotels, such as the Arlington. But the railroad didn’t eliminate the dangers for visitors; it just fundamentally altered their nature. The threat landscape shifted from the opportunistic violence of the trail to the systemic, internal corruption of the city itself. The predators no longer had to wait for you in the woods; they were waiting for you right on the station platform.

The “Doctor Drummers”

Perhaps the most insidious threat awaiting new arrivals was the uniquely Hot Springs predator known as the “doctor drummer.” These weren’t musicians; they were aggressive solicitors for unscrupulous physicians who swarmed the trains the moment they arrived. Spotting anyone who looked ill or infirm, they would descend with promises of miraculous cures, steering the sick and desperate toward a specific doctor for a kickback.

This was a ruthlessly efficient, organized system of patient trafficking designed to monetize the suffering of the city’s most vulnerable visitors. The practice became so widespread that the federal government was eventually forced to intervene. The official 1900 Rules and Regulations for Government of the Hot Springs Reservation explicitly prohibited “the payment of any sum of money or anything of value from drumming,” which is the clearest possible evidence that this wasn’t just a nuisance, but a structured, profitable, and deeply corrupt enterprise. For countless invalids who had exhausted their savings to get to the spa, their first welcome was a can man looking to make a buck off their misery.

The Bunco Artists & Crooked Cops

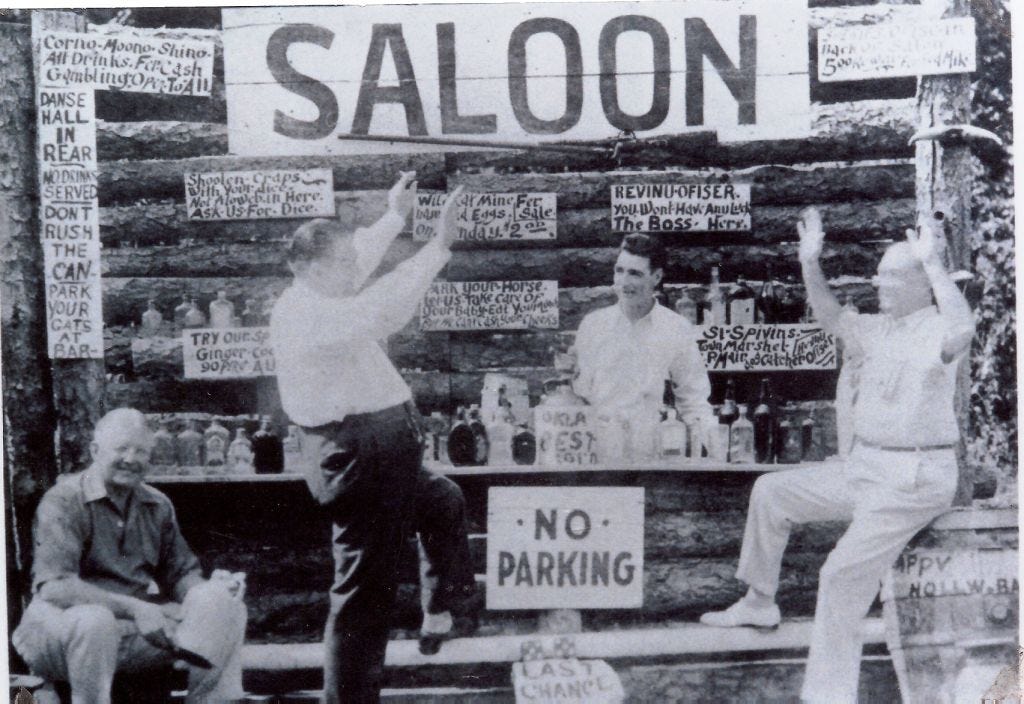

Alongside the medical grifters, Hot Springs teemed with a host of confidence men, swindlers, and “bunco steerers” who worked to fleece newcomers of their savings. Gangs set up shop right in Malvern to run crooked dice and card games for passengers waiting between trains. In Hot Springs, “bunco steerers” were deployed at the depots and hotels to identify wealthy-looking strangers and lure them into rigged gambling games.

What made this threat so terrifying was that the law wasn’t on the victim’s side. These swindling operations were often protected by the local police, who had been bought and paid for by the gambling bosses. If a tourist - or “mark” - realized he’d been cheated and dared to complain to the authorities, the police would frequently arrest the victim himself on a fabricated charge. Surviving the outlaws on the trail was one thing; arriving in a city where the man with the badge was part of the conspiracy was another entirely. The gauntlet didn’t end at the city limits; it just got more sophisticated.

The Peak and The Turning Point: When the Lawmen Went to War

If the grifters at the train station represented the city’s opportunistic corruption, the open warfare that defined its power structure was something else entirely. This wasn’t just crime; this was a series of violent corporate takeovers for control of Hot Springs’s most profitable, albeit illegal, industry: gambling. For much of the late 19th century, the city’s streets served as the battlefield for brutal turf wars where the line between lawman and outlaw wasn’t just blurred - it was nonexistent.

The Flynn-Doran War

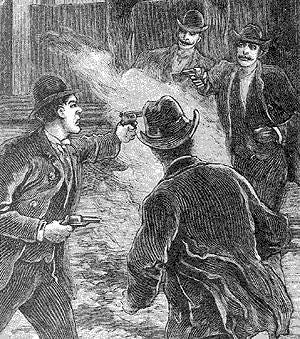

By the early 1880s, Frank “Boss Gambler” Flynn had established a comfortable monopoly over the city’s rackets. He maintained his dominance by effectively using the Hot Springs Police Department as his private Army to intimidate rivals and collect debts. But his grip was challenged by a new faction led by the formidable Major S.A. Doran, a former Confederate officer with a reputation for deadly violence. The resulting conflict, known as the Flynn-Doran War, plunged the city into chaos.

The audacity of the violence was stunning. The war featured public duels, the hiring of out-of-state gunmen, and even a brazen assassination attempt where Flynn’s men rented a room in the prestigious Arlington Hotel to set up a sniper’s nest to kill Doran as he walked to dinner. The conflict reached its bloody climax on February 9, 1884, when Doran’s faction ambushed Flynn and his brothers in their buggy on Central Avenue. The ensuing firefight, waged with shotguns and rifles in broad daylight, left multiple men dead and wounded, including innocent bystanders caught in the crossfire. In a testament to the absolute power of the gambling syndicates, all the arrested participants were eventually acquitted on grounds of self-defense, a verdict so outrageous that disgusted citizens formed their own militia to restore some semblance of order.

When the Badge Became the Target

As incredible as a war between gambling syndicates was, it was merely the prelude to the city’s ultimate civic implosion. On March 16, 1899, the streets of Hot Springs became a battlefield for a gunfight not between outlaws and lawmen, but between the Hot Springs Police Department and the Garland County Sheriff’s Office. The cause was shockingly simple: the two law enforcement agencies were at war over who would control the city’s gambling graft and the lucrative kickbacks that came with it.

The violence erupted when Garland County Sheriff Bob Williams and his son confronted and opened fire on a police sergeant on Central Avenue. The fight escalated into a chaotic melee outside a saloon, where officers, deputies, and their relatives engaged in a furious gun battle. When the gunsmoke cleared, five men lay dead. The dead included Police Chief Thomas Toler, Sergeant Tom Goslee, and Detective Jim Hart - all shot and killed by the Sheriff’s faction. The Sheriff’s own son, Johnny, was also killed in the exchange. This wasn’t just a breakdown of law and order tearing itself apart for a piece of the action. The very men sworn to protect the public had become the city’s most dangerous and unpredictable threat, fighting to the death for their share of the city’s foundation of vice.

A Legacy of Lawlessness

The gunsmoke from the 19th century’s brutal turf wars eventually cleared, but it left behind something far more durable than shell casings: a perfectly crafted system of institutionalized corruption. The chaos of the Flynn-Doran era and the absurdity of the Police-Sheriff shootout weren’t just a wild phase; they were the violent forging of the city’s political DNA. From these ashes rose an airtight, locally run political machine that perfected the art of profiting from vice while maintaining a veneer of civic order. This powerful machine created the unique environment that would later make Hot Springs the unofficial vacation capital for America’s most notorious 20th-century gangsters.

This is the most misunderstood part of the city’s history. Mobsters like Al Capone, Charles “Lucky” Luciano, and Owney Madden didn’t run Hot Springs - they were just allowed to vacation here. The local political machine, led for decades by figures like Mayor Leo P. McLaughlin, was fiercely proprietary. They kept the lucrative corruption strictly in-house, and outside mobs weren’t welcome to a piece of the action. The arrangement was simple: visiting gangsters were welcome as long as they behaved, spent their money freely, and, most importantly, left the locals alone. Upon arrival, a gang would often send an emissary to the police department to announce their presence and make a “contribution” to the Policeman’s Benevolent Fund.

Anyone who mistook this hospitality for weakness learned a quick, hard lesson. In the 1930s, the brutish Chicago mobster Joe “Polack” Saltis attempted to move in and establish his own gambling operation. The local machine didn’t send hitmen; they simply used the system. The gambling czar, W.S. Jacobs, denied him permission. Then, the local authorities “threw the book” at him, raiding his tavern and hitting him with a barrage of charges for everything from possessing illegal firearms to not having the right license plates. A local judge, a key player in the machine, issued a permanent injunction that effectively put him out of business. Utterly defeated, the “dangerous mobster” packed his bags and left town. The legacy of the 19th century was a perfectly insulated bubble of vice, a town that was both wide-open and fiercely, jealously controlled.

The Enduring Paradox of the Spa

So, what are we to make of 19th-century Hot Springs? Was it the federally sanctioned sanctuary for healing, or a lawless frontier town that operated on bribes and bullets? The messy, uncomfortable, and thoroughly entertaining truth is that it was both. At the very same time, the government was building bathhouses for the indigent, and the Army was establishing the nation’s first combined military hospital; the city’s streets were echoing with the gunfire of warring syndicates, and its elected officials were busy auctioning off justice to the highest bidder.

This is the enduring paradox that lies at the very soul of Hot Springs. The promise of healing was inextricably bound to the peril of a lawless frontier. The very qualities that made it a premier national destination - its wealth and constant influx of hopeful visitors - were the same qualities that fueled the brutal conflicts over its illicit economies.

This history of high-stakes corruption and Wild West violence matters because it’s the story behind the story. It explains how a town could become a respectable, federally managed health resort and, simultaneously, a capital of vice so perfectly insulated that it became the preferred neutral ground for America’s most dangerous mobsters. The wild, contradictory spirit of Hot Springs wasn’t born in the 20th century with the arrival of the mob; it was forged in the 19th century, in the gunsmoke of the trails, in the back alleys where grifters fleeced the sick, and in the shocking street battles between the lawmen themselves.

If you enjoyed this trip into the wild past of Hot Springs, share this article with a friend or upgrade your subscription for more hidden histories from the Spa City.

References

Abbott, S. (2006). The Bookmaker's Daughter: A Memory Unbound. University of Arkansas Press.

Adler, P. (2006). A House Is Not a Home. University of Massachusetts Press.

Allbritton, O. E. (1996). A city drenched in blood. The Record, 37, 23–37.

Allbritton, O. E. (2006). Hot Springs Gunsmoke. Garland County Historical Society.

Allbritton, O. E. (2008). Dangerous Visitors: The Lawless Era. Garland County Historical Society.

Allbritton, O. E. (2009). The Mob at the Spa: Organized Crime and Its Fascination with Hot Springs, Arkansas. Garland County Historical Society.

A bloody affray. (1899, March 17). Daily Arkansas Gazette, p. 1. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014801/1899-03-17/ed-1/seq-1/

Brown, D. (1982). The American Spa: Hot Springs, Arkansas. Rose Publishing Company.

Harbour, D. (2011, September 21). James-Younger gang hits Hot Springs. Wooden Nickel. https://woodennickel.wordpress.com/stories/james-younger-gang-hits-hot-springs/

Harrigan, S. (1991, April). The double life of Hot Springs. American Heritage, 42(2). https://www.americanheritage.com/double-life-hot-springs

Hill, D. (2020). The Vapors: A southern family, the New York mob, and the rise and fall of Hot Springs, America's forgotten capital of vice. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Hill, T. (n.d.). The almost shoot out of 1884. National Park Service. Retrieved August 6, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/the-almost-shoot-out-of-1884.htm

History runs deep at Arkansas' Hot Springs National Park. (2024, July 18). AAA Club Alliance. https://cluballiance.aaa.com/the-extra-mile/series/the-extra-mile-magazine/mountain-miracle

Hot Springs, Arkansas, the 'valley of vapors'. (n.d.). Legends of America. Retrieved August 6, 2025, from https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ar-hotsprings/

The history of Hot Springs, Arkansas. (n.d.). Hotsprings.org. Retrieved August 6, 2025, from https://www.hotsprings.org/explore/history/

The hot springs drummer. (1881, January 25). Daily Arkansas Gazette, p. 2. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014801/1881-01-25/ed-1/seq-2/

James-Younger Gang. (n.d.). HistoryNet. Retrieved August 6, 2025, from https://www.historynet.com/james-younger-gang/

Library of Congress. (1888). Bird's-eye-view of Hot Springs, Arkansas [Map]. Geography and Map Division. https://www.loc.gov/item/75694005/

Lindeman, B. (1964, September 19). Showdown in Arkansas: No dice in Hot Springs. The Saturday Evening Post.

Maurer, D. W. (1940). The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man. The Bobbs-Merrill Company.

National Park Service. (n.d.). History & culture. Hot Springs National Park. Retrieved August 6, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/index.htm

National Park Service. (2024). When did it happen? A Hot Springs chronology. U.S. Department of the Interior.

Pfanz, H. W. (1957). History of Hot Springs National Park. National Park Service.

Raines, R. K. (2013a). Hot Springs, Arkansas. Arcadia Publishing.

Raines, R. K. (2013b). Hot Springs: From Capone to Costello. Arcadia Publishing.

Sifakis, C. (2001). Flynn-Doran War. In The Encyclopedia of American Crime (2nd ed.). Facts on File.

Stage robbery. (1874, January 17). Daily Arkansas Gazette, p. 1. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014801/1874-01-17/ed-1/seq-1/

State Historical Society of Missouri. (n.d.). Cole Younger. Historic Missourians. Retrieved August 6, 2025, from https://shsmo.org/historic-missourians/cole-younger

U.S. Department of the Interior. (1900). Rules and Regulations for the Government of the Hot Springs Reservation. Government Printing Office.

What is a ‘drummer’?. (1907). Dialect Notes, 3(3), 134. American Dialect Society.