Gunfight at the Spa: The 1899 Hot Springs Massacre

The bloody true story of the day the Hot Springs Police and the Garland County Sheriff's Office went to war over control of the city's gambling rackets.

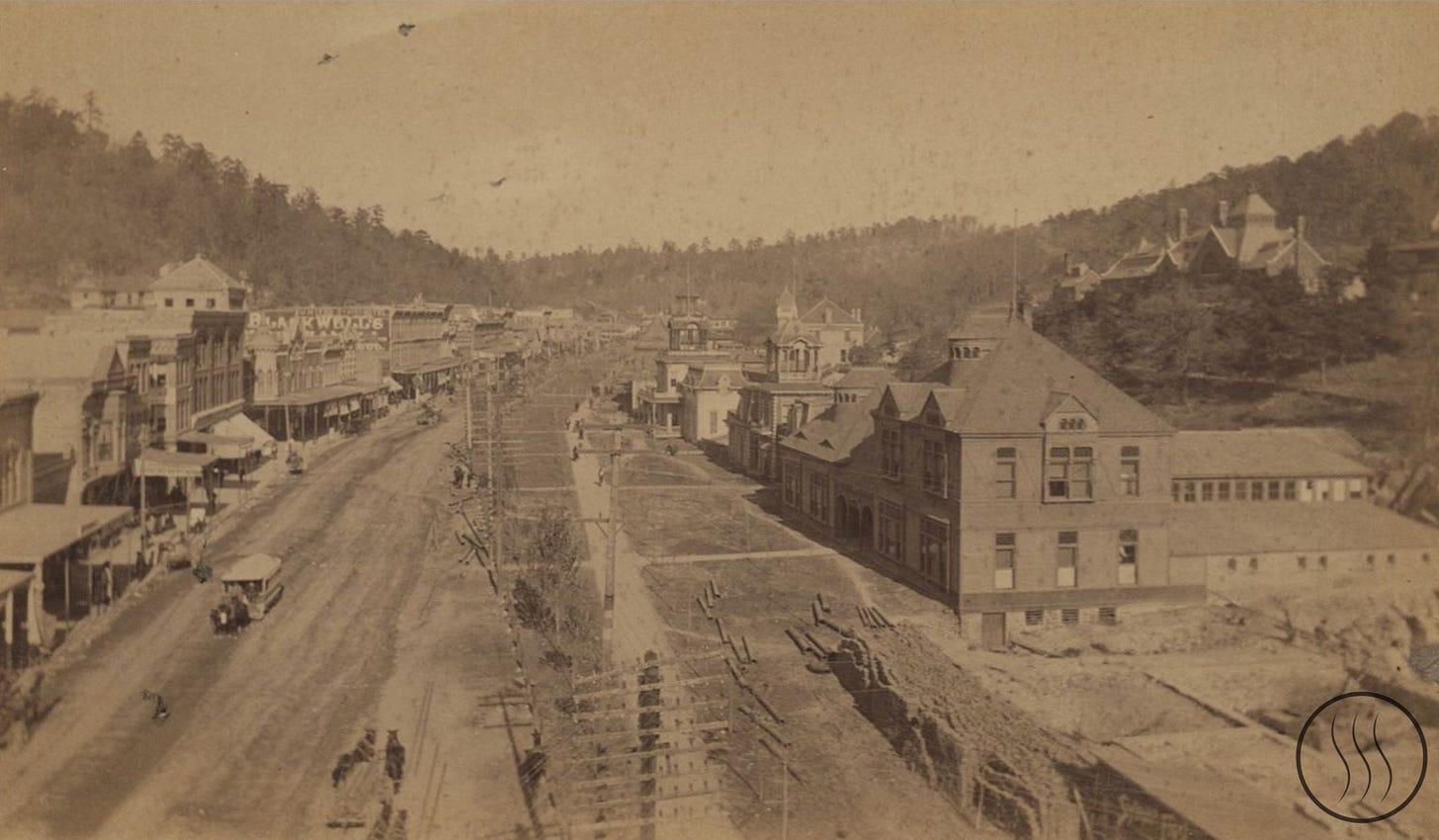

On March 16, 1899, Hot Springs, Arkansas, wasn’t exactly a picture of civic tranquility. Instead, it erupted into a street war so intense it made a soap opera look dull. The conflict wasn’t between the law and outlaws, but a classic showdown over who would control the city’s thriving and “wide-open” gambling scene. The combatants were the Hot Springs Police Department and the Garland County Sheriff’s Office - think of it as an old-school crime, but the rival gangs were the ones with the badges.

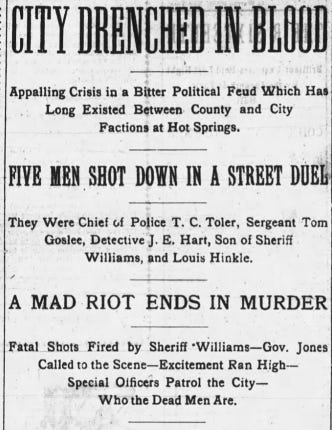

When the dust finally settled, five men were dead, including the Chief of Police. The grand finale featured the public execution of a respected city detective - courtesy of the County Sheriff himself. Who knew local law enforcement could have such a flair for theatrics?

The Morning of the Gunfight

The morning of Thursday, March 16, 1899, began not with gunfire but with the quiet background dealings that truly ran Hot Springs. The city was in the grip of a heated mayoral election, a contest that was less about civic duty and more about who would control the city’s most profitable industry: its openly operating gambling rackets.

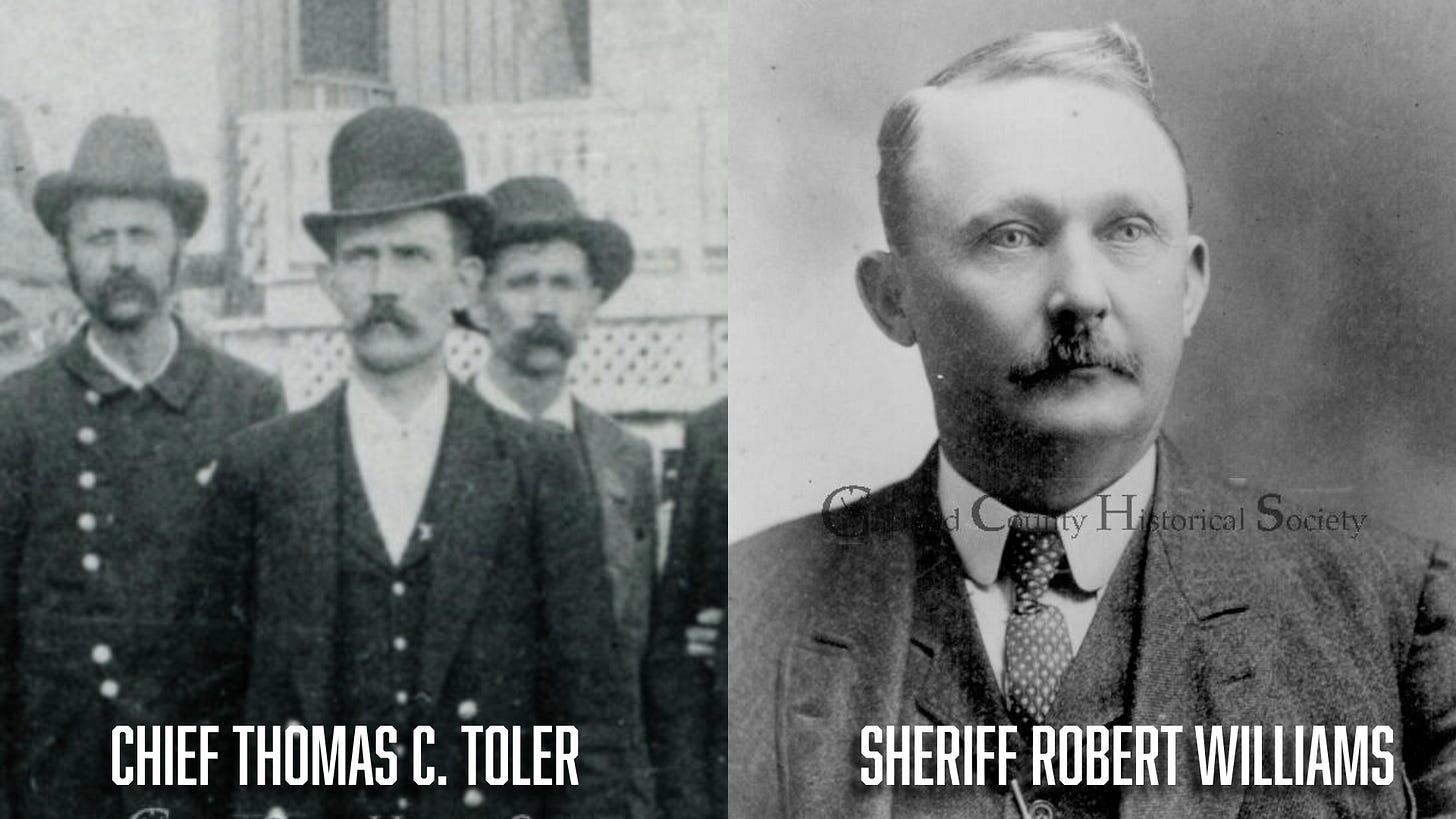

On one side of this political chess match was the powerful Garland County Sheriff, Robert “Bob” Williams. He had thrown his support behind the incumbent mayor in exchange for a simple promise: upon re-election, the mayor would fire the current police chief and install the Sheriff’s brother, “Coffee” Williams, in his place. This move would give the Williams family near-total control over the flow of money and power in the city.

On the other side was the man on the chopping block, Hot Springs Chief of Police Thomas C. Toler. A veteran of the city’s political wars, Toler wasn’t about to let his career and influence be dismantled without a fight. That morning, he held what sources called a “political caucus” at City Hall, gathering his officers to formally throw the police department’s support behind a rival candidate, C.W. Fry, who had promised Toler he could keep his job if Fry won.

It was a bold declaration of war against the Sheriff, and word traveled fast. One of the men in Toler’s meeting - whose identity remains a mystery to this day - immediately communicated the details of the political betrayal to Sheriff Williams at the courthouse. Angered by this direct threat to his political and business arrangement, the Sheriff left the courthouse and headed downtown.

The First Shots: Approx. 1:30 PM

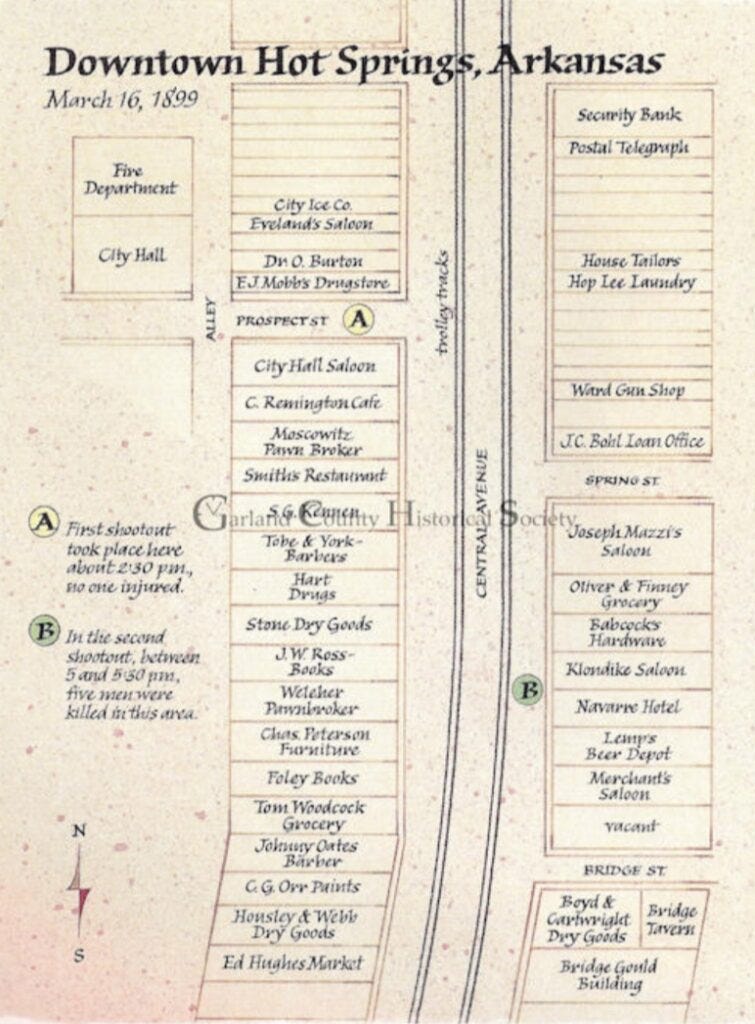

The Sheriff’s anger found its target just after lunch. Hot Springs Police Sergeant Tom Goslee, a trusted subordinate of Chief Toler, had just finished getting a haircut at Tobe & York’s barbershop on Central Avenue. As he stepped out onto the street, he saw Sheriff Williams across the way, standing in front of Joe Mazzia’s Saloon and talking with a friend and deputy, Dave Young. As Goslee turned to head back to City Hall, Williams spotted him.

“Tom, Tom Goslee,” the Sheriff called out, beckoning him over.

Goslee crossed the street. Williams, holding a folded piece of paper with the names of the officers from Toler’s meeting, furiously demanded to know why Goslee was working against him. The argument escalated until Williams called the sergeant “a liar and a coward” and made a threatening move, reaching into his coat.

Goslee reacted instantly. He drew the only weapon he had on him - a small, two-shot derringer - and warned the Sheriff, “I will defend myself if forced to”. Seeing that a gunfight was imminent, Dave Young jumped between the two men, pushing them apart and briefly stopping the fight.

The confrontation should have ended there. Goslee, seeing the Sheriff was momentarily unarmed, turned to walk away. But Williams wasn’t finished. He crossed the street toward the City Hall Saloon, where he had seen his son, Johnny, enter minutes before. The younger Williams saw his father approaching and met him in the street near the trolley tracks. After a brief exchange, Johnny handed his father his .44 revolver and then borrowed another pistol from an acquaintance.

Now armed, the father-and-son duo opened fire on Sgt. Goslee. The street erupted with the sound of fourteen shots being exchanged. Goslee fired his two rounds and miraculously escaped the volley, retreating past the office of Justice W.A. Kirk and darting down an alley to the Sumpter House for cover. The first battle was over, but the consequences were just beginning. District Prosecuting Attorney David M. Cloud immediately began taking statements from witnesses. Based on this, he promptly issued a warrant for the arrest of Sheriff Williams, who, though unhappy with the decision, immediately posted bond. The county’s chief lawman was now officially a defendant, setting the stage for the day’s final, far bloodier chapter.

The “Truce” & The Massacre

The shootout on Central Avenue between the Sheriff and Sgt. Goslee sent a tremor through Hot Springs. For the city’s business owners and political operators, this wasn’t just a spat between lawmen; it was a threat to the bottom line. Panicked tourists meant empty hotel rooms and quiet casinos. The pressure mounted quickly. Mayoral candidate C.W. Fry warned Chief Toler that something had to be done to restore peace before it further damaged the local economy.

Toler agreed. A series of phone calls were made to broker a peace meeting. Toler instructed Sgt. Goslee to call Johnny Williams to arrange a truce, while he, in turn, would call Sheriff Williams for the same purpose. They agreed to meet around 5 pm in front of Lemp’s Beer Depot, a saloon three doors north of Bridge Street, to “shake hands and have a drink.”

The Meeting at Lemp’s

Just before 5 pm, two trios of armed men converged on Central Avenue. From the north, representing the Hot Springs Police, came Chief Tom Toler, Captain Lee Haley, and Sergeant Tom Goslee. From the south, for the Garland County Sheriff’s Office, came Chief Deputy Coffee Williams, Deputy Ed Spear, and the Sheriff’s son, Johnny Williams.

For a fleeting moment, peace seemed possible. The initial greetings were reportedly “cordial”. Johnny Williams and Tom Goslee, who had been shooting at each other just hours before, even stepped forward and shook hands. However, any appearance of peace was short-lived.

The flimsy truce was deliberately shattered by Toler’s own man, Captain Lee Haley. Leaning against the bar, Haley directed a pointed accusation at Deputy Ed Spear. “I understand you have said that if I put my head out, you would blow it off.” Spear, irritated, shot back, “Anybody who said that is a goddamn liar.”

This exchange enraged the bartender, Louis Hinkle, who happened to be Captain Lee Haley’s brother-in-law. In an act of loyalty that would’ve been commendable were it not for the knife in his hand, Hinkle screamed, “Don’t make me out a liar,” vaulted over the bar, grabbed Spear from behind, and slashed his throat with an open Budweiser souvenir knife.

The Massacre

The slice of Hinkle’s knife unleashed a torrent of gunfire.

The badly wounded Deputy Ed Spear wrestled free from Hinkle’s grasp, drew his pistol, and fired a shot into the bartender’s neck.

Almost simultaneously, Coffee Williams drew his own revolver and fired a second, fatal shot into Hinkle’s chest, killing him.

Across the sidewalk, Johnny Williams pulled his pistol and shot Sgt. Goslee twice, once in the groin and once in the knee.

As he fell, the dying Goslee managed to fire his own pistol one last time. His aim was true; the bullet struck Johnny Williams in the head, a mortal wound.

Chief Deputy Coffee Williams then stepped toward the fallen police sergeant and fired a third, final shot into the body of Tom Goslee, executing him.

In a stunning display of cowardice, Captain Lee Haley fled the scene, abandoning his chief, Tom Toler, and leaving the body of his brother-in-law, Louis Hinkle, on the sidewalk. His flight left Chief Toler outgunned and completely alone. Toler fought back, pulling his revolver and exchanging fire with Coffee Williams, who took cover behind a parked express wagon, and the severely bleeding Ed Spear. Toler managed to wound Spear in the shoulder. As he maneuvered for a better position, however, he was struck by two bullets almost at the same instant: one to the head from Coffee Williams’s pistol, and one to the chest from Ed Spear’s revolver. Either shot would have been fatal. Chief Toler fell dead on the sidewalk, the final casualty of the massacre at Lemp’s.

The Final Act & The Aftermath

The gun smoke from the massacre at Lemp’s was still hanging in the air when Garland County Sheriff Bob Williams arrived on the scene, accompanied by his nephews, deputies Will and Sam Watt. He came upon a scene of pure carnage; four men, including his rival, Chief Toler, lay dead or dying on the blood-soaked sidewalk. His eyes quickly found the body of his own son, Johnny, who was still breathing but had suffered a mortal head wound. The Sheriff’s grief, sources say, immediately curdled into a cold and vengeful rage.

The Murder of a Good Cop

At that moment, Detective James E. Hart of the Hot Springs Police Department was just arriving. Hart, a respected former police chief, had been at the city’s train station on official business when he was alerted to the shootout. He was responding to restore order to the chaos. He was, by all accounts, one of the few straight-arrow cops in a crooked town, a man with a blind wife and three small children at home.

He never had a chance.

Sheriff Williams saw him approaching. In an act of stunning brutality, the Sheriff strode up to the detective, grabbed the lapel of his coat, and snarled, “Here’s another of those sons of bitches.”

He then shoved his .45 Colt revolver in Hart’s face and fired twice. Though Detective Hart was armed, the attack was so sudden and vicious that he had no time to react. As the detective collapsed, the Sheriff’s nephew, Will Watt, stepped around his uncle and fired two more shots into Hart’s lifeless body.

The Aftermath

The fifth killing within an hour triggered a stampede among the crowd of onlookers. The city plunged into chaos. As news of the massacre spread, frightened tourists rushed to catch the next trains. The city officials, seeing their profits disappear, were reportedly enraged. They hurriedly sent a telegram to Arkansas Governor Dan Jones, begging him to come and restore order. The governor left for Hot Springs on a special train at 2 am the next morning, and his personal presence helped calm the community. To address the immediate crisis, the new acting police chief appointed 150 special officers to patrol the streets and prevent further violence.

Amidst this civic chaos, local Constable Sam Tate arrived with a large freight wagon to perform the grim task of collecting the bodies from the street and delivering them to the mortuary. Mrs. Toler, the chief’s widow, made her way through the turmoil and confronted Sheriff Williams directly. Unmoved, the Sheriff reportedly told her, “Yes, we got Toler, and I wish we had you where we’ve got him.” Stunned, she retreated to her apartment, retrieved her husband’s loaded pistol, and returned intending to kill the Sheriff herself, but by then, he was gone. Later that night, around 9 pm, Johnny Williams died from his wound, bringing the day’s death toll to five.

The legal proceedings that followed were a masterclass in Garland County justice. The surviving members of the Williams faction were charged with murder, but in a series of trials that defied the testimony of dozens of eyewitnesses, every single one of them was acquitted or released after juries deadlocked. A few months after the shootout, Detective Hart’s blind widow, Emma L. Hart, filed a $20,000 lawsuit against Sheriff Williams for the wrongful death of her husband. She lost.

The Williams Family had won the war. Their victory, secured with bullets on Central Avenue and ratified by a compliant legal system, solidified a new and even more ruthless control over the city’s profitable rackets, ensuring Hot Springs’s place as a gangster’s paradise for the next half-century.

References

Allbritton, O. E. (2006). Hot Springs gunsmoke. Garland County Historical Society.

Calm after storm. (1899, March 18). Arkansas Democrat, p. 1.

City drenched in blood. (1899, March 17). Arkansas Democrat, p. 4.

Damage suit filed. (1899, August 6). Daily Arkansas Gazette, p. 1.

Five men killed! (1899, March 17). Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, p. 1.

Five men shot to death. (1899, March 17). Daily Arkansas Gazette, p. 1.

Held without bond. (1899, March 19). Daily Arkansas Gazette, p. 1.

The lawmen's war: Corruption, conspiracy, and the 1899 Hot Springs gunfight. (n.d.). [Unpublished research report].

No further trouble feared. (1899, March 18). Daily Arkansas Gazette, p. 1.

Quiet at Hot Springs. (1899, March 19). Fort Smith Times, p. 6.