We Bathe the World: The Unseen Labor of the American Spa

How a hidden army of skilled laborers built and sustained an iconic American industry through its golden age.

If you stepped off the train in Gilded Age Hot Springs, you’d be forgiven for thinking you’d stumbled into paradise. Here, tucked away in the rugged Arkansas Ouachitas, was the famed “American Spa.” It was a world-renowned resort, a place where the nation’s elite came to chase away their ailments in clouds of thermal steam. Captains of industry, senators, and celebrities all flocked here. Marble-lined bathhouses stood like temples. Grand hotels offered every luxury imaginable. The entire valley hummed with the promise of health, leisure, and rejuvenation.

But none of it - not one single bit - ran on magic.

That opulent world was built, plumbed, and scrubbed by a massive, unseen army of laborers. For every millionaire soaking in a porcelain tub, a bath attendant was working a ten-hour day in sweltering heat - an attendant who had trained extensively in hygiene and anatomy. For every grand hotel, there were hundreds of builders, maids, and porters whose toil was the invisible foundation of its luxury. This glittering enterprise didn’t just appear out of thin air. It was constructed, piece by painstaking piece, by a skilled working class whose story is now buried under the very promenade they built.

The history of Hot Springs is usually told through its famous visitors - the gangsters, the presidents, the baseball players. This Labor Day, we’re telling a different story. It’s a story found behind the bathhouse walls, in the neighborhoods the tourists never saw, and in the lives of the people who made it possible. Grab a cup of coffee. You’re going to want to hear this.

Building a Town from Scratch

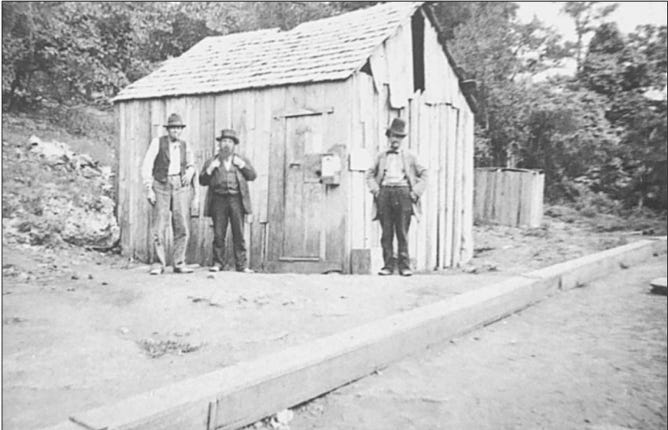

Before the Gilded Age put a tuxedo on it, Hot Springs was a place of powerful contradictions. For thousands of years, Native American tribes had revered the “valley of the vapors” as a neutral ground for healing. When the first American explorers arrived in 1804, they found a place already known, dotted with crude shelters built by people seeking the legendary cure. Everyone knew this place was special. The problem was that it was also a rustic, primitive, and brutally remote outpost.

The US government certainly recognized its value. In an act of remarkable foresight, Congress set aside the land as the Hot Springs Reservation in 1832. That made it America’s first federally protected natural resource, a full forty years before Yellowstone became the first official National Park. In a move of almost perfect government logic, however, after setting it aside, Congress promptly forgot to pass any laws for actually administering the place for decades. This, naturally, created a glorious mess.

This legal limbo shaped the town’s unique character. While Arkansas was a slave state, the federal reservation status made a large enslaved population unfeasible; that rule was, surprisingly, consistently enforced. Hot Springs wasn’t built on a plantation economy; its currency was service and trade. This created a rare and distinct environment. The town attracted a significant population of free African Americans seeking economic opportunities that were simply unavailable in the surrounding agricultural regions. This early community of entrepreneurs and laborers laid the foundation for the vibrant social and business district that would one day become known as “Black Broadway.” It wasn’t a utopia, but for many, it was the best opportunity around.

Still, life in the early settlement was tough. The first “hotel” was a simple dogtrot log cabin, and by the 1830s, the town was little more than “four wretched-looking log cabins.” The first “baths” were rough-hewn wooden tubs or, more often, simple cavities in the rock screened by a few bushes. Then, just as the ramshackle town was gaining steam, the Civil War swept through and burned it to the ground, leaving it abandoned and in ruins. The residents who straggled back after 1865 had to start all over again, tasked with building their unique community, for a second time, from the ashes up.

The Rise to Prominence: Engineering an Elegant Spa City

After the Civil War, Hot Springs had a serious identity crisis. It had the miracle waters, sure. But it was also caught in a tangled web of conflicting land claims that prevented real progress. Finally, in 1876, the US Supreme Court slammed its gavel down. The verdict was simple: the springs belonged to the federal government. That single act was like cracking a dam. Investment and federal oversight poured into the valley, ready to transform the rough-and-tumble town into an elegant, profitable resort.

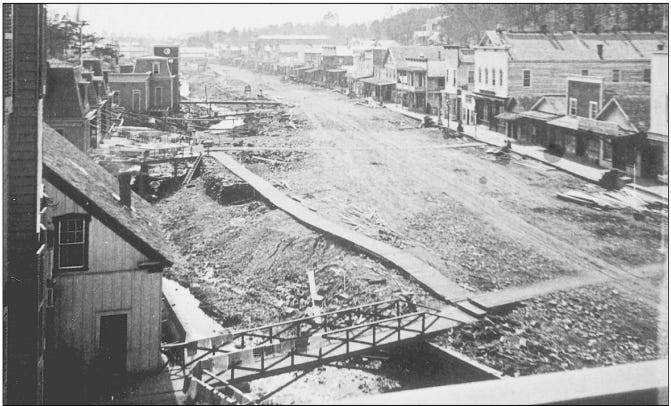

Mother Nature, in a remarkable act of timing, decided to aid in the urban renewal. A devastating fire ripped through the town in March 1878, destroying most of the old wooden buildings. It was a disaster, but many locals saw it as a blessing in disguise. The fire cleared the way for a grander, more substantial city to rise from the ashes.

The first monumental task? Dealing with the town’s dirty little secret. Hot Springs Creek. For decades, this stream had served as an open sewer and garbage dump. It was a stinking health hazard - not a great look for a world-class resort. So, between 1882 and 1884, a massive engineering project was launched to tame it. Hundreds of laborers, in a feat of pure grit, enclosed the entire creek in a 3,500-foot underground arch. They buried the problem once and for all, literally paving over an open sewer to create the pristine, manicured promenade of Bathhouse Row. You have to appreciate the priorities.

All this construction and federal money meant one thing: jobs. And the workers building this new spa city weren’t about to be left out of the prosperity they were creating. On November 22, 1882, seven men met in a blacksmith’s shop. They formed the city’s first assembly of the Knights of Labor, the era’s most powerful labor organization. Then, in a sign of the complex times, members of that group helped charter a second, separate assembly for the city’s African American workers just a few weeks later. From the very beginning, the hands that built the spa were determined to have a voice in it.

The Golden Age: A Day in the Life of a Bath Attendant

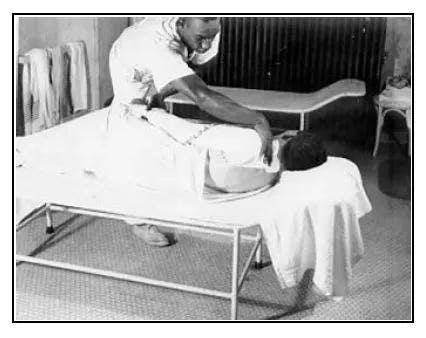

Forget the fluffy robes and cucumber water. A trip to one of the grand bathhouses wasn’t a relaxing spa day; it was a prescribed medical treatment. Visitors didn’t just show up and ask for a soak; they arrived with a doctor’s written prescription in hand. These weren’t suggestions. They were specific, technical instructions detailing precise water temperatures, the duration of the bath, and the methods of treatment. And the person responsible for reading that doctor’s scrawl and administering that treatment perfectly? The bath attendant.

This is why becoming an attendant was so difficult. It was a licensed profession, and the training was intense. The Department of the Interior ran a mandatory school where applicants had to pass rigorous exams in anatomy, physiology, hygiene, and first aid - tests that, by all accounts, were equivalent to a nursing exam. The federal government even established a Federal Registration Board to certify the physicians who were allowed to prescribe the baths in the first place. The entire system, from top to bottom, was structured like a medical practice.

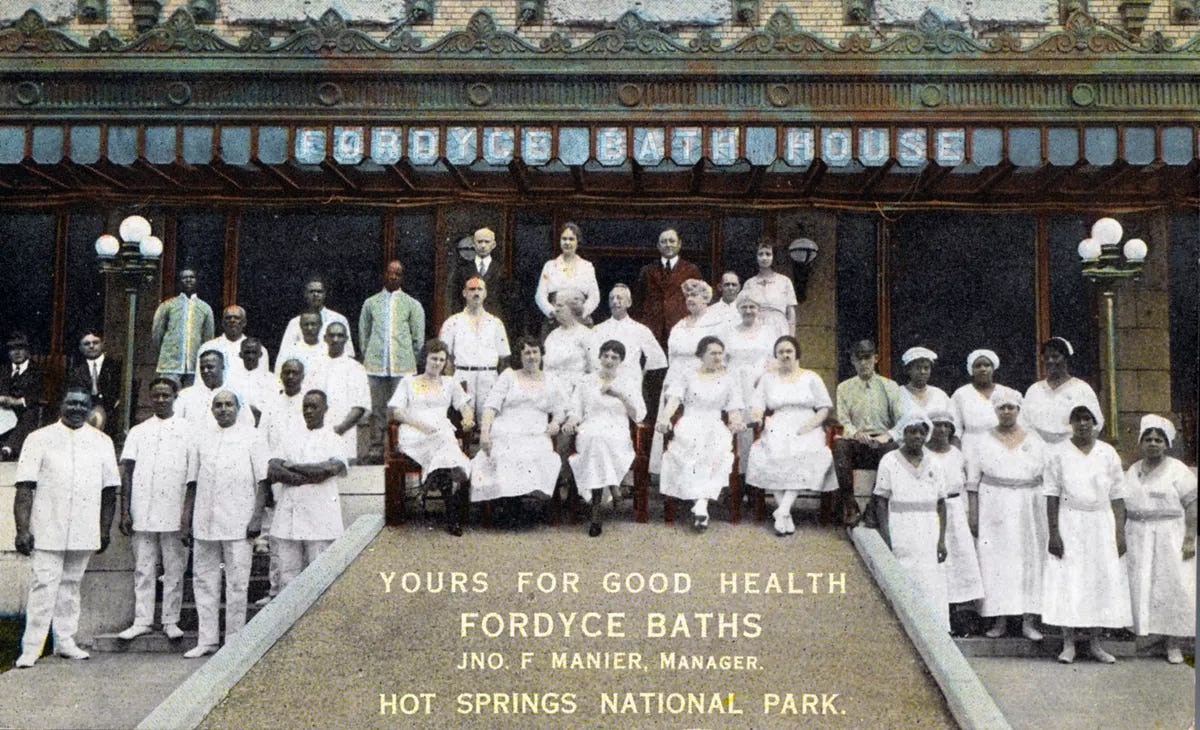

Not all bathhouses were created equal, of course. A job at a top-tier house like the Fordyce, Maurice, or Buckstaff was the pinnacle of the profession. Those coveted spots were often passed down through families or earned after years of building an impeccable reputation at smaller establishments. Your name and your skill were everything.

The daily grind was grueling. An attendant might handle 30 to 40 different prescriptions a day in perpetual, sweltering humidity. One of the most demanding treatments was “packing.” According to attendant Iola Bedford, this involved taking heavy towels soaked in 147°F mineral water, wringing them out by hand, and wrapping them tightly around a patient’s afflicted areas. It was scalding, exhausting work.

But here’s the part of the story that often gets lost—the reward for that skill and toughness could be astonishing. Because official wages were low, the entire system ran on tips. A skilled attendant with a loyal clientele of “regulars” could do exceptionally well. In 1915, a top attendant could earn up to $20 per week in wages and tips - significantly more than the $7 a week a white female clerk might make in another industry. Some regulars were so devoted to their attendants that they’d bestow lavish gifts, from new suits of clothes to all-expense-paid trips to New York.

This created a bizarre paradox. In the rigidly segregated Jim Crow South, Black attendants held a unique form of para-medical authority. But that didn’t change the world outside the bathhouse. Attendant Katherine Tate, while trusted to administer complex treatments at the opulent Fordyce, was still required to eat her lunch in the basement. It was a world of contradictions - a place where you could be a respected professional and a second-class citizen all in the same afternoon.

Community and Legacy: Life Beyond the Bathhouse Walls

The workday had to end sometime. The steam cleared, and the tourists returned to their grand hotels. The attendants, porters, and laborers of the American Spa also went home. But what did they do for fun? In a town built to entertain the world’s elite, the working class - both Black and White - carved out a vibrant world of their own. They didn’t just build the resort; they created a lively city culture that buzzed with energy long after the bathhouses locked their doors.

For entertainment, Hot Springs was an absolute playground. The whole town caught baseball fever every spring when Major League teams like the Chicago Cubs and Boston Red Sox rolled in for spring training. For the price of a ticket, a bartender or a bricklayer could watch legends like Babe Ruth knock a ball clear out of Whittington Park. Speaking of Whittington Park, it was the city’s very own Coney Island, complete with the state’s largest rollercoaster, prize fights, and political rallies. And, of course, there were the wonderfully bizarre tourist attractions, such as the Ostrich Farm and Alligator Farm, which were just as popular with locals as they were with visitors.

While many of these amusements were shared, the realities of a segregated South meant that the African American community also built a remarkable, self-sufficient world. Centered on Malvern Avenue, their vibrant business district became known as “Black Broadway.” When they were barred from the premier bathhouses, they didn’t just accept it. They financed and constructed their own, like the handsome Pythian and the magnificent Woodman of the Union building. The Woodman complex was a cultural center unto itself, boasting a first-class hotel, a hospital, and a 2,000-seat theater that hosted top entertainers, including Count Basie.

The people themselves were more than their job titles. Lewis “Snook” Wesson was a skilled bath attendant who also played professional baseball. Fred W. Martin rose from a laborer to become an elected official. The legacy of the Hot Springs workforce isn’t just the gleaming resort they maintained. It’s the resilient, multi-faceted, and thoroughly American community they forged for themselves in the heart of the Valley of the Vapors.

Raising a Glass to the Working Class

The stories of Hot Springs are usually told in whispers about Al Capone’s favorite suite or the Gilded Age millionaires who strolled Bathhouse Row. We love those stories, of course. But that’s not the real foundation of the city. Not even close.

The “American Spa” wasn’t built on gambling money or old fortunes. It was built on the grit of the men who buried a creek, the incredible skill of the attendants who turned bathing into a medical craft, and the daily toil of thousands of maids, porters, builders, and drivers who kept the whole fantastic machine running. They were the engine, often unseen and uncredited, that powered the resort through its golden age. Their legacy is the city itself—a monument not just to luxury, but to the dignity and resilience of American labor.

This history is a vital part of what makes Hot Springs unique. If you found this story compelling, please share it with a friend who loves a good hidden history.

And to help us continue digging through the archives for more stories like this and to join the conversation in the comments, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Your support is what keeps these files open.

References

Allbritton, O. E. (2003). Leo & Verne: The Spa's Heyday. Garland County Historical Society.

Allbritton, O. E. (2006). Hot Springs Gunsmoke. Garland County Historical Society.

Anthony, I. B. (2011). A place apart: A pictorial history of Hot Springs, Arkansas. University of Arkansas Press.

Arkansas Department of Transportation. (2020, October). Gulpha Gorge Bridges (Nos. 1-4).

Bedinger, M. S. (1974). Valley of the Vapors: A Natural History of Hot Springs. Eastern National Park and Monument Association.

BiblioVault. (n.d.). Arkansas's Gilded Age: The Rise, Decline, and Legacy of Populism and Working-Class Protest. University of Missouri Press. Retrieved from https://www.bibliovault.org/BV.book.epl?ISBN=9780826221667

Brown, D. (1982). The American Spa: Hot Springs, Arkansas. Rose Publishing Company.

Chmil, D. (2023, November 15). Hot Springs National Park uncovers stories, impact of bathhouse attendants. In M. Johnson, THV11.

City of Hot Springs. (1898). A Directory of the City of Hot Springs.

Covington, M. W. (2001). Freedom's Steaming Ground: Slavery, Federal Land, and the Free Black Community of Antebellum Hot Springs. The Record, 32, 45-62. Garland County Historical Society.

Dewitt, J. (2001). The Business of the Cure: A Social and Economic History of the Hot Springs Bathhouse Industry. Journal of Southern History, 67(3), 561-590.

Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (n.d.-a). Hot Springs (Garland County). Retrieved from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/hot-springs-887/

Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (n.d.-b). Hot Springs Fire of 1905. Retrieved from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/hot-springs-fire-of-1905-12570/

Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (n.d.-c). Hot Springs National Park. Retrieved from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/hot-springs-national-park-2547/

Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (n.d.-d). Knights of Labor. Retrieved from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/knights-of-labor-3595/

Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (n.d.-e). Labor Movement. Retrieved from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/labor-movement-4235/

Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (n.d.-f). Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900. Retrieved from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/post-reconstruction-through-the-gilded-age-1875-through-1900-402/

Garland County Historical Society. (2024). African-American Bathhouse Employees & Their Contributions to Local History. Retrieved from https://garlandcountyhistoricalsociety.com/program/african-american-bathhouse-employees-their-contributions-to-local-history/

Graves, J. W. (1990). Town and Country: Race Relations in an Urban-Rural Context, Arkansas, 1865–1905. University of Arkansas Press.

Hanley, R. (2015). Hot Springs: Past and present. University of Arkansas Press.

Hild, M. (2018). Arkansas's Gilded Age: The Rise, decline, and legacy of populism and working-class protest. University of Missouri Press.

Hot Springs Convention & Visitors Bureau. (n.d.). History of Hot Springs, Arkansas. Retrieved from https://www.hotsprings.org/explore/history/

Hot Springs Daily News. (1882, November 28). The Labor Question: Knights of Labor Organize a Colored Assembly.

Hot Springs Daily News. (1888, January 22). The Bathhouse Question.

Miller, S. (2011). Constructing the 'American Spa': Landscape, Labor, and Segregation in Hot Springs, Arkansas. The Public Historian, 33(2), 55-78.

National Park Service. (n.d.-a). Brief summary of park history. NPS History. Retrieved from https://npshistory.com/publications/hosp/chronology.pdf

National Park Service. (n.d.-b). Hot Springs National Park. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/bibe/learn/historyculture/hotsprings.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.-c). Oral history collection. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/oral-history-collection.htm

National Park Service. (1985). Katherine Tate Oral History Interview. Hot Springs National Park Archives.

National Park Service. (1988). Ernest Lemons Oral History Interview. Hot Springs National Park Archives.

National Park Service. (2021, August 4). Oral history transcript: Claudine Adams. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/upload/Claudine%20Adams.doc

National Park Service. (2021, August 4). Oral history transcript: lola Bedford. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/upload/lola%20Bedford.doc

National Park Service. (2024, May 8). Building an African American community at Hot Springs. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/articles/building-african-american-community-hot-springs.htm

National Park Service. (2024, November 2). Profiles from the past. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/profiles-from-the-past.htm

National Park Service. (2025, February 19). The history of Bathhouse Row. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/bathhouse-row.htm

National Park Service. (2025, February 19). We Bathe the World: Recording African American histories. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/we-bathe-the-world.htm

Paige, J. C., & Greene, L. W. (1987). Out of the Vapors: A Social and Architectural History of Bathhouse Row. U.S. Government Printing Office.

Roberts, L. (2005). Gender, Race, and the Intimate Labor of the Cure in the New South. Journal of Women's History, 17(1), 123-145.

Scully, F. J. (1966). Hot Springs, Arkansas and Hot Springs National Park. Pioneer Press.

The Sentinel-Record. (1908, March 15). Colored Men Organize: Knights of Pythias to Erect a Handsome Bathhouse.

Unique Coloring. (n.d.). Hot Springs and the Black experience. Retrieved from https://www.uniquecoloring.com/articles/hot-springs-and-blacks

United States Congress. House. (1890). Investigation of Hot Springs Affairs. U.S. Government Printing Office.

United States Department of the Interior. (1914). Rules and Regulations for the Government of All Bath Houses Receiving Hot Water from the Hot Springs Reservation, Ark. U.S. Government Printing Office.

United States Department of the Interior. (Annual Reports, 1885-1905). Report of the Superintendent of the Hot Springs Reservation to the Secretary of the Interior. U.S. Government Printing Office.

West, C. (2021). The oldest national park? A history of Hot Springs, Arkansas [Video]. YouTube.

Wikipedia. (n.d.). History of Arkansas. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Arkansas

Works Progress Administration. (1941). The WPA Guide to 1930s Arkansas. Viking Press.

Zavodny, M. (2019). Review of Arkansas's Gilded Age: The Rise, Decline, and Legacy of Populism and Working-Class Protest, by M. Hild. Labour / Le Travail, 84, 331-333. https://www.lltjournal.ca/index.php/llt/article/view/5966/6831