Before Al Capone made it his southern headquarters, before the first Gilded Age millionaire soaked their weary bones, and long before the first European stumbled through the Ouachita Mountains looking for gold, the Valley of Vapors had a different kind of power. It was a place known for its magic water and its strict, simple rule: leave your weapons at the door.

The story of Hot Springs, Arkansas, doesn’t start with gangsters or gamblers. It starts thousands of years earlier, with a piece of land so special, so revered, that even warring tribes agreed it was off-limits for violence. This isn’t just the story of a town; it’s the story of a sanctuary.

The Valley of the Vapors: A 10,000-Year-Old Health Spa

Archaeological evidence tells us that people have been visiting this valley for at least 10,000 years. They came for the water. Bubbling out of 47 different springs at a piping hot 143°F, the water was seen as a gift from the “Great Spirit,” who was believed to live in the valley. The steam that gave the Valley of Vapors its name was thought to be the Creator’s own breath.

And honestly, you can’t blame them for thinking it was magic. For people in a pre-medical world, a spring of naturally sterile, hot water was a miracle. It could clean a wound, soothe aching joints, and treat all manner of skin ailments. It was, for all intents and purposes, America’s first and oldest health spa, drawing pilgrims from hundreds of miles away who came to heal in the sacred water and mud.

The Original Neutral Ground

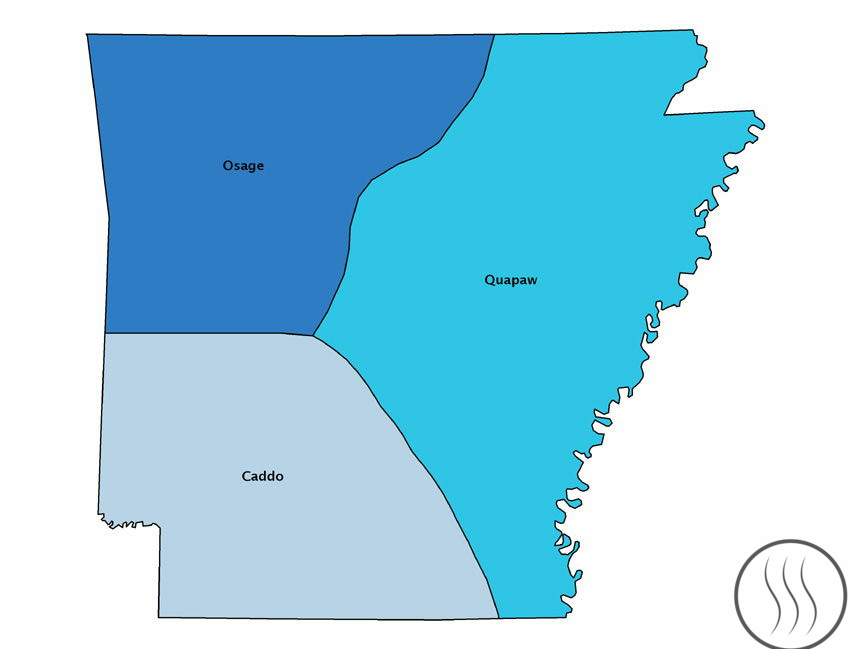

Because the valley was considered sacred, it came with a very important rule: you didn’t fight there. For centuries, the Valley of Vapors was an established neutral ground. A warrior from the Caddo tribe could be soaking his feet just a stone’s throw from a warrior from the Quapaw, and they would leave each other in peace. It was a sanctuary where all grievances were temporarily suspended in favor of healing.

Oddly enough, this ancient concept of a “safe zone” would be resurrected thousands of years later. When the gangsters of the 1920s and ‘30s came to Hot Springs, they operated under a similar truce. It was the one place in America where a guy from Capone’s Outfit could have a drink next to a guy from the New York mob without worrying about getting a shiv in the ribs. The valley, it seems, has always been a convenient place for people to agree not to kill each other.

More Than a Spa: The “Silicon Valley” of the Stone Age

While the water healed the body, the mountains provided the tools for survival. The hills around Hot Springs are packed with novaculite, an incredibly hard and dense type of flintstone, perfect for making sharp-edged tools and weapons. Think of it as the Silicon Valley of the Stone Age.

For thousands of years, tribes like the Tunica operated quarries here, chipping away at the “Arkansas Stone” to create arrowheads, knives, and scrapers. The quality was so exceptional that these tools were traded across a network that stretched all the way to the Great Plains and the Gulf Coast. This made the Valley of Vapors not just a spiritual destination, but a vital center of industry and technology—a place where you went to get the best gear on the market.

First Contact: When the Old World Crashed the Party

This ancient world of peace and industry was violently interrupted in 1541. The Spanish expedition led by Hernando de Soto came crashing through Arkansas, not for a spa day, but for gold. While local legend insists De Soto himself bathed in the springs, there’s no real proof. His men were conquistadors, and the valley’s true treasures - healing and high-quality stone - were lost on them.

The first documented American visit came in 1804, when the Hunter-Dunbar Expedition was sent by Thomas Jefferson to see what he’d gotten in the Louisiana Purchase. They didn’t find an empty wilderness. They found a place already in use as a health resort, with a log cabin and crude shelters built by people who still knew the old stories - that this was a place you came to for relief. The American chapter was about to begin, but the valley’s identity as a sanctuary was already thousands of years old.

Resources

Lund, John W. . "Historical Impacts of Geothermal Resources on the People of North America." Geo-Heat Center Bulletin October 1995: 7-14. PDF. 12 January 2022. <https://oregontechsfstatic.azureedge.net/sitefinity-production/docs/default-source/geoheat-center-documents/quarterly-bulletin/vol-16/art2.pdf?sfvrsn=4b3f8d60_4>.

“History & Culture.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 30 Sept. 2021, Retrieved 12 January 2022. https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/index.htm.

Sloan, D. (1992). The Expedition of Hernando De Soto: A Post-Mortem Report. The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 51(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/40038199

Benson, F. M., & Libby, D. S. (n.d.). History of Hot Springs National Park. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/hosp/hot_springs_history.pdf

De Soto, Gambling, Resorts and the Mob: A history of Hot springs. (2012 January 01). Hot Springs Guest Guide. https://www.hsguestguide.com/post/14/de-soto-gambling-resorts-and-the-mob-a-history-of-hot-springs

De Soto Expedition, Route of the - Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (2023, May 4). Encyclopedia of Arkansas. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/route-of-the-de-soto-expedition-7679/

Visit Hot Springs. (n.d.). History Museums, Gangster Era, Historic Bathhouse Row - Things To Do. Retrieved from https://www.hotsprings.org/

Hunter-Dunbar Expedition - Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (2023, July 28). Encyclopedia of Arkansas. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/hunter-dunbar-expedition-2205/