Hot Springs, Arkansas, has always been a town of fascinating contradictions. In 1832, it was set aside as the nation’s first federal reservation, a protected sanctuary for the healing thermal waters that bubbled up from the earth’s core. It branded itself “The American Spa,” a world-class health resort where presidents, industrial titans, and high society came to soothe their ailments in magnificent, marble-clad bathhouses. But behind the respected facade of steam rooms and doctors’ prescriptions existed a parallel, and arguably more profitable, industry. This was the Hot Springs where you could get a fine steak, a bad bet, and a good time, not always in that order.

History loves to focus on the famous gangsters who made the Spa their personal playground - men like Owney Madden, Al Capone, and Lucky Luciano, who treated the city as a neutral ground where they could vacation without fear of a rival’s bullet. But to say the Mob ran Hot Springs is to miss the point entirely. The city’s lucrative rackets were a homegrown affair, managed by a fiercely independent machine of local politicians and operators who controlled who could play and how the game was played. And in the most intimate corners of this shadow economy, the real power belonged to a group of shrewd, iron-willed entrepreneurs who have been all but erased from the story: the madams.

These weren’t just women on the fringes of the underworld; they were formidable business executives who built and managed sophisticated empires of vice. In the “open town” of Hot Springs, they operated as quasi-legitimate proprietors, appearing in court to pay regular “fines” that everyone understood to be a city-sanctioned amusement tax. The most famous of them all, Maxine Temple Jones, transformed a $1000 investment into a powerhouse enterprise, with her flagship brothel, “The Mansion,” catering to a clientele of judges, senators, and top-tier mobsters alike. These women were the queens of the city’s other hospitality industry, wielding a unique brand of economic influence and social authority. This is the story of how they did it.

The Origins: A Spa Town with a Shadow Economy

Before it was a notorious hideout, it was a sanctuary. The story of Hot Springs always begins with the water - the 700,000 gallons of 143-degree thermal goodness that bubbles up daily from the Ouachita Mountains. Native American tribes considered the “Valley of the Vapors” neutral ground for healing. In 1832, the US government made it the nation’s first federal reservation, a place set aside for public health and wellness. By the late 19th century, this official stamp of approval had turned the town into “The American Spa,” a world-class resort packed with grand hotels and palatial bathhouses. This legitimate, thriving industry attracted a constant stream of wealthy patrons, high-society tourists, and ailing invalids - all with plenty of time on their hands and money in their pockets. It was the perfect recipe for a shadow economy. Vice didn’t just corrupt Hot Springs; it grew up right alongside the bathing industry like a slightly sinister, and far more profitable, twin sister.

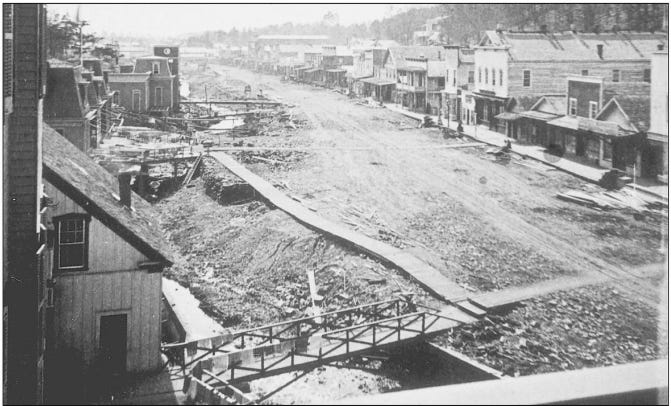

This shadow economy was never a secret; it was a contested prize. The city’s early history reads less like a story of civic development and more like a corporate turf war fought with six-shooters. The 1880s were defined by the infamous Flynn-Doran feuds, a bloody conflict between rival gambling entrepreneurs fighting for control of the town’s rackets. The combatants, “Boss Gambler” Frank Flynn and the notoriously deadly Major S.A. Doran, imported their own private armies of gunfighters, turning Central Avenue into an armed camp. When the smoke cleared from their final, bloody ambush in 1884, one gambler and two innocent bystanders lay dead in the street, but the business of vice marched on. These weren’t just random acts of violence; they were brutal business negotiations that established a simple fact: in Hot Springs, crime wasn’t just organized, it was the primary organizing principle.

If there was any doubt about who truly ran the town, it was settled on March 16, 1899, in one of the most astonishing gunfights in American history. This wasn’t a battle between cops and robbers. This was a battle between the cops and the other cops. The Hot Springs Police Department, led by Chief Tom Toler, and the Garland County Sheriff’s Office, led by Sheriff Bob Williams, opened fire on each other in the middle of Central Avenue. The issue? Control over the city’s gambling profits. The gunfight, which left five men dead - including the police chief, a sergeant, and a detective - made it brutally clear that local law enforcement wasn’t there to stop vice, but to regulate it for their benefit. This was the world the great madams would inherit: a city where corruption was the status quo, where the authorities were just another faction to be managed, and where a savvy entrepreneur with enough nerve could build an empire. They didn’t have to invent the system; they just had to perfect it.

The Rise to Prominence: The “Open Town” & The Queen

The messy, ad-hoc corruption of the early days was destined to be perfected. It just needed an architect. That man was Leo Patrick McLaughlin, a charismatic political boss who got himself elected mayor in 1927 on a refreshingly honest platform: he promised to run Hot Springs as an “open town.” And for 20 years, he delivered. McLaughlin’s political machine was a thing of beauty in its own brazen way. He controlled elections by monopolizing poll tax receipts - a prerequisite for voting at the time - and was known to get a little help from voters whose names could only be found in the local cemetery. This absolute control of the Garland County vote gave him a powerful bargaining chip in state politics. He could deliver the county to any gubernatorial candidate who was willing to make a simple promise: leave Hot Springs the hell alone. And they did. For two decades, state laws against gambling and prostitution simply ceased to exist at the Hot Springs city limits.

This political protection allowed for the creation of a truly unique and sophisticated system. The madams and casino operators weren’t treated like common criminals. They were, for all intents and purposes, licensed business owners. On a regular basis, they would parade into municipal court to pay their “fines,” which everyone in on the joke understood to be an “amusement tax” or a business licensing fee. This revenue, in turn, funded the city. It paved the streets and paid the salaries of the very policemen who might occasionally have to raid a house for show. Vice became an unofficial public utility. This stable, predictable environment was a paradise for an ambitious entrepreneur, and in 1948, the woman who would become its queen arrived for a visit and decided to stay.

Her name was Maxine Temple Jones, and she was a world away from the debutantes taking the waters on Bathhouse Row. Born into the poverty of rural Arkansas, she was a tomboy with a taste for fancy things and an iron will to acquire them. After a brief and boring stint as a department store clerk, she found a much faster path to financial independence in the world’s oldest profession. She honed her skills in Texarkana under the tutelage of an established madam named Nell Raborn, learning the art of the deal and the importance of having “strong nerves.” A tour of duty in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps during World War II, where she earned the nickname “the Blonde Bomber,” gave her a worldly edge her competitors lacked.

Maxine was a shrewd observer. When she landed in Hot Springs, she saw a system practically begging to be mastered. She took a job working at a brothel at 105 1/2 Prospect Avenue, a surprisingly respectable street known for its fine homes. But she had no intention of working for someone else for long. A masterful manager of her own money, she saved up her earnings. Then, in 1950, she made her move. She bought the entire business from her boss for the princely sum of $1000. The very night she became a “landlady,” she worked alongside her girls, but that was the last time. From that moment on, she was purely management. The reign of Maxine Jones had begun.

The Peak & The Turning Point: Mansions & Mobsters

With the system perfected and protection assured, the madams of Hot Springs entered their golden age. This was the era of Maxine Jones, undisputed queen of the city’s vice. Having established herself at the Prospect Street house, she was making so much money that she decided to expand. She purchased a large, 14-room, two-story home on Palm Street for $15,000 and transformed it into the most elegant and exclusive brothel the state had ever seen. This was “The Mansion,” and it was here that her legend was forged. Jones curated an atmosphere of pure class. Her employees were dressed in expensive, formal dinner gowns, and the clientele was strictly A-list. On any given night, you might find local doctors, prominent businessmen, state senators, and federal judges mingling with some of the most famous gangsters in America. The money flowed like water. Jones claimed to clear up to $5000 in a single night - an astronomical sum in the 1950s. She wasn’t just a madam; she was the CEO of a thriving, high-end hospitality enterprise.

While Maxine Jones built an independent kingdom, other women found power through direct alliance with the underworld. Grace Goldstein, the common-law wife of the notorious bank robber Alvin “Creepy” Karpis, ran a different kind of operation. Her brothel, the “Hatterie Hotel,” was more than a business; it was a criminal headquarters. It served as a safe house where Karpis and his associates could lie low and plan their next move, shielded by a police force that was thoroughly compromised. Goldstein’s most legendary contribution to the city’s lore was her “dinner bell” warning system. According to the stories, when federal agents - the only lawmen the locals couldn’t buy - were spotted on the edge of town, Goldstein would ring a bell. The signal would ripple through the community, a town-wide alarm alerting every resident outlaw to disappear into the woodwork. It was a perfect illustration of the deep, symbiotic corruption that defined the Spa; the entire town was in on the secret.

But this insulated world couldn’t last forever. The very success of Hot Springs’s homegrown rackets eventually attracted the attention of more powerful forces. A national crime syndicate, seeing a river of cash flowing out of the Ouachita Mountains, decided they wanted a piece of the action. They approached Maxine, who by now was the most powerful madam in the region, and tried to muscle her into their organization, demanding a cut of her profits in exchange for “protection” she neither needed nor wanted. It was a fatal miscalculation on their part. They underestimated the country girl’s grit. Jones, who had built her empire from nothing, flatly refused to be extorted. “I’m not going to give my money to the syndicate,” she told them. “I pay my money to the city, and I think that’s enough.”

It was a brave stand, but it marked the beginning of the end. The fragile shield of local protection she had so carefully maintained shattered. The syndicate used its influence to turn the local authorities against her. Suddenly, the madam who had operated with impunity for years found herself harassed, raided, and targeted. The system she had mastered was now being used as a weapon to destroy her. In 1963, Maxine Jones was convicted on prostitution charges and sentenced to two years in prison - a fate she saw as being a “political prisoner” of the Mob she defied. The queen had been toppled from her throne.

The Later Years & Lasting Legacy: Pardons & Crackdowns

When Maxine Jones was released from prison in 1965, the empire she had built was in ashes. She was broke, her health was shattered, and her beautiful home had been lost to foreclosure. The criminal machine she had defied had, for a time, won. But a new political wind was blowing through Arkansas, and its name was Winthrop Rockefeller. The new governor, a reform-minded Republican, was determined to do what his predecessors had only pretended to do: dismantle the state’s entrenched political machines, with Hot Springs being his prime target. Maxine, ever the strategist, saw her opportunity. In a move of breathtaking audacity, the former convict turned state’s witness, providing Rockefeller’s administration with inside information on the city’s illegal gambling operations. It was the ultimate power play. In exchange for her cooperation, Governor Rockefeller granted Maxine Jones a full pardon, wiping her criminal slate clean. With her freedom secured, she promptly bought the Central Hotel and got right back to business.

The comeback, however, was short-lived. The world that had allowed her to flourish was on its last legs. Unlike the governors before him, Rockefeller wasn’t bluffing. In 1967, in a series of decisive raids, he ordered the Arkansas State Police to permanently shut down all illegal gambling in Hot Springs. This wasn’t a temporary shakedown for a bigger payoff; it was a final, unceremonious end. Slot machines and gaming tables that had spun and clicked for decades were unceremoniously smashed and burned. The crackdown was devastating. Without the magnetic pull of the high-stakes casinos, the steady stream of high-rollers, gangsters, and thrill-seekers dried up. The entire shadow economy buckled. For the city’s madams, the business model was broken. Their clientele was gone. By 1971, Maxine Jones finally closed up shop for good, marking the definitive end of an era.

So, what is the legacy of these women? It’s complicated. It’s tempting to romanticize them as trailblazing feminist entrepreneurs, and there’s a case to be made. In a time when a woman’s professional options were laughably limited, they built financial empires from scratch, managing complex logistics, dangerous employees, and even more dangerous clients with remarkable skill. Maxine Jones, in particular, operated with a level of executive authority that was virtually unheard of for a woman of her generation. But their power was always conditional, a “contingent agency” granted by the very patriarchal system they seemed to challenge. Their businesses were built on the bodies of other women, and their security was purchased from male politicians and lawmen—protection that was revoked the moment she challenged the authority of more powerful men in the syndicate. They were neither saints nor simple sinners. They were master survivors, savvy capitalists who saw a corrupt system and, instead of fighting it or fleeing, they bent it to their will for as long as they could.

Why the Madams Still Matter

The story of the Hot Springs madams is more than just a titillating glimpse into a bygone world of sin. It’s a uniquely American story of enterprise, power, and survival, set in a town built on paradox. For half a century, these women ran sophisticated, profitable businesses in plain sight, navigating a treacherous landscape of corrupt politicians, local lawmen, and visiting gangsters. They were businesswomen in an era that offered women few opportunities, and they commanded a peculiar form of respect in a world that officially condemned them. They weren’t just accessories to the city’s infamous history; they were central figures who shaped its economy and its reputation.

Their reign was sustained by a fragile, homegrown system of corruption that ultimately couldn’t withstand outside pressures. When political tides shifted and the final raids occurred, their era ended as definitively as it had started. What remains is a complex legacy. Were they liberated entrepreneurs or cogs in an exploitative machine? The truth, as is often the case, lies somewhere in the messy, intriguing middle. The story of Maxine Jones and her peers serves as a powerful reminder that power takes many forms, and that the most compelling parts of history are often hidden just beneath the surface.

Did you enjoy this peek into the Spa City's hidden history? If so, please consider sharing this article with a friend who loves a good story. For more deep dives into the forgotten corners of the past, be sure to subscribe.

References

Allbritton, O. E. (2006). Hot Springs Gunsmoke. Garland County Historical Society.

Brown, D. (1982). The American Spa: Hot Springs, Arkansas. Rose Publishing Co.

Hanley, R. (2011). A Place Apart: A Pictorial History of Hot Springs, Arkansas. University of Arkansas Press.

Hill, D. (2020). The Vapors: A Southern Family, the New York Mob, and the Rise and Fall of Hot Springs, America's Forgotten Capital of Vice. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Jones, M. T. (1983). Maxine "Call Me Madam": The Life and Times of a Hot Springs Madam. Hot Air Publishing.

National Park Service. (2024). When Did It Happen? A Chronology of Historic Events at Hot Springs National Park.

Ramsey, P. (2000). A place at the table: Hot Springs and the GI Revolt. The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 59(4), 407-428.

Raines, R. (2013). Hot Springs: From Capone to Costello. Arcadia Publishing.

Research Report. (n.d.). Meet the Madams: The Women Who Ran Hot Springs's Hospitality Industry.

Scully, F. J. (1966). Hot Springs, Arkansas, and Hot Springs National Park. Pioneer Press.

Teske, S. (2024). Leo Patrick McLaughlin (1888–1958). In Encyclopedia of Arkansas. CALS. Retrieved from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/leo-patrick-mclaughlin-1712/

Teske, S. (2024). Maxine Temple Jones (1915-1997). In Encyclopedia of Arkansas. CALS. Retrieved from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/maxine-temple-jones-5338/

Teske, S. (2024). Sex Work. In Encyclopedia of Arkansas. CALS. Retrieved from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/sex-work-4553/

Ye Hot Springs, Arkansas, Picture Booke. (1894). Woodward & Tiernan Printing Company.

Arkansas Department of Heritage. (2023). Chronicling America Digitized Newspapers. Retrieved from https://www.arkansasheritage.com/chronicling-america-digitized-newspapers

Arkansas State Archives. (2021). National Digital Newspaper Program. Retrieved from https://www.arkansasheritage.com/blog/dah/2021/09/29/national-digital-newspaper-program

Bridges, K. (2024, August 20). History minute: Leo McLaughlin and the fall of Hot Springs' corruption. Arkadelphian. Retrieved from https://arkadelphian.com/2024/08/20/history-minute-leo-mclaughlin-and-the-fall-of-hot-springs-corruption/

Brown, D. (1982). The American Spa: Hot Springs, Arkansas. Rose Publishing Co.

Christ, M. (2023, June 12). Encyclopedia of Arkansas Minute: Maxine Temple Jones. UALR Public Radio. Retrieved from https://www.ualrpublicradio.org/2023-06-12/encyclopedia-of-arkansas-minute-maxine-temple-jones

Clancy, S. (2024, June 11). The Vapors. In Encyclopedia of Arkansas. CALS. Retrieved from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/the-vapors-book-15429/

Friedman, B. (2015). 30 Illegal Years To The Strip.

Garland County Historical Society. (n.d.). Holdings. Retrieved from https://garlandcountyhistoricalsociety.com/holdings/

Garland County Historical Society. (n.d.). Publications. Retrieved from https://garlandcountyhistoricalsociety.com/publications/

Garland County Historical Society. (2011). The Mob at the Spa: Organized Crime and Its Fascination with Hot Springs, Arkansas. Retrieved from https://garlandcountyhistoricalsociety.com/product/the-mob-at-the-spa-organized-crime-and-its-fascination-with-hot-springs-arkansas/

Goodspeed Publishing Co. (1889). Biographical and historical memoirs of Pulaski, Jefferson, Lonoke, Faulkner, Grant, Saline, Perry, Garland and Hot Spring counties, Arkansas.

Henry, L. (2019, June 4). Hot Springs is soaked in Mob lore. The Mob Museum. Retrieved from https://themobmuseum.org/blog/hot-springs-is-soaked-in-mob-lore/

Jobb, D. (2020, October 29). The rise and fall of a Southern hotbed of vice. Southern Review of Books. Retrieved from https://southernreviewofbooks.com/2020/10/29/the-vapors-david-hill-review/

Lancaster, G. (Ed.). (n.d.). Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Central Arkansas Library System.

Lancaster, G., & Thrasher, C. (2019). The Murder of Oscar Chitwood.

Library of Congress. (n.d.). Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Retrieved from https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/

National Park Service. (n.d.). Archives. Hot Springs National Park. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/archives.htm

Nix, J. B. (2020). The Ohio Club: Local Landmark Gets a Facelift. The Record, 61, 9.1–9.6.

Ramsey, P. (2000). A place at the table: Hot Springs and the GI Revolt. The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 59(4), 407–428.

Raines, R. (2013). Hot Springs: From Capone to Costello. Arcadia Publishing.

Teske, S. (2024, June 20). GI Revolt. In Encyclopedia of Arkansas. CALS. Retrieved from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/gi-revolt-4157/

Teske, S. (2024, May 29). Leo Patrick McLaughlin (1888–1958). In Encyclopedia of Arkansas. CALS. Retrieved from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/leo-patrick-mclaughlin-1712/

Teske, S. (2024, May 29). Maxine Temple Jones (1915–1997). In Encyclopedia of Arkansas. CALS. Retrieved from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/maxine-temple-jones-5338/

Teske, S. (2024, June 17). Sex Work. In Encyclopedia of Arkansas. CALS. Retrieved from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/sex-work-4553/

Wenger, R. C. (2017). Tuskegee, Public Health, and Venereal Disease in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Southern Spaces. Retrieved from https://southernspaces.org/2017/tuskegee-public-health-and-venereal-disease-hot-springs-arkansas/

Williams, C. G. (2023, February 27). Arkansas Backstories: Maxine. AY Magazine. Retrieved from https://aymag.com/arkansas-backstories-maxine/