Jefferson’s “Other” Expedition

Before Lewis and Clark returned, Jefferson had another team exploring the Louisiana Purchase. Their target? The mysterious "hot waters of the Washita." This is their story.

Everyone knows the story of Lewis & Clark, right? The epic 2 1/2-year slog across the continent, the Corps of Discovery, Sacagawea, and the Pacific Ocean - it’s a foundational American epic. But what if I told you it wasn’t their report that gave President Thomas Jefferson his first real scientific glimpse into the massive territory he’d just bought?

That’s right. Before anyone in Washington, DC had heard a word from the snow-bound explorers on the Missouri River, a different dispatch from the brand-new Louisiana Purchase landed on Jefferson’s desk. It was a meticulously detailed, deeply scientific report from a forgotten expedition—a journey not to the Pacific, but to a place far stranger, a place Native Americans called the “Valley of Vapors.”

The mission, commissioned by Jefferson in 1804, was led by two men who couldn’t have been more different. The first was William Dunbar, a wealthy Mississippi planter, slave owner, and one of the most respected scientific minds in the American South—an astronomer and surveyor so brilliant that he corresponded regularly with Jefferson himself.

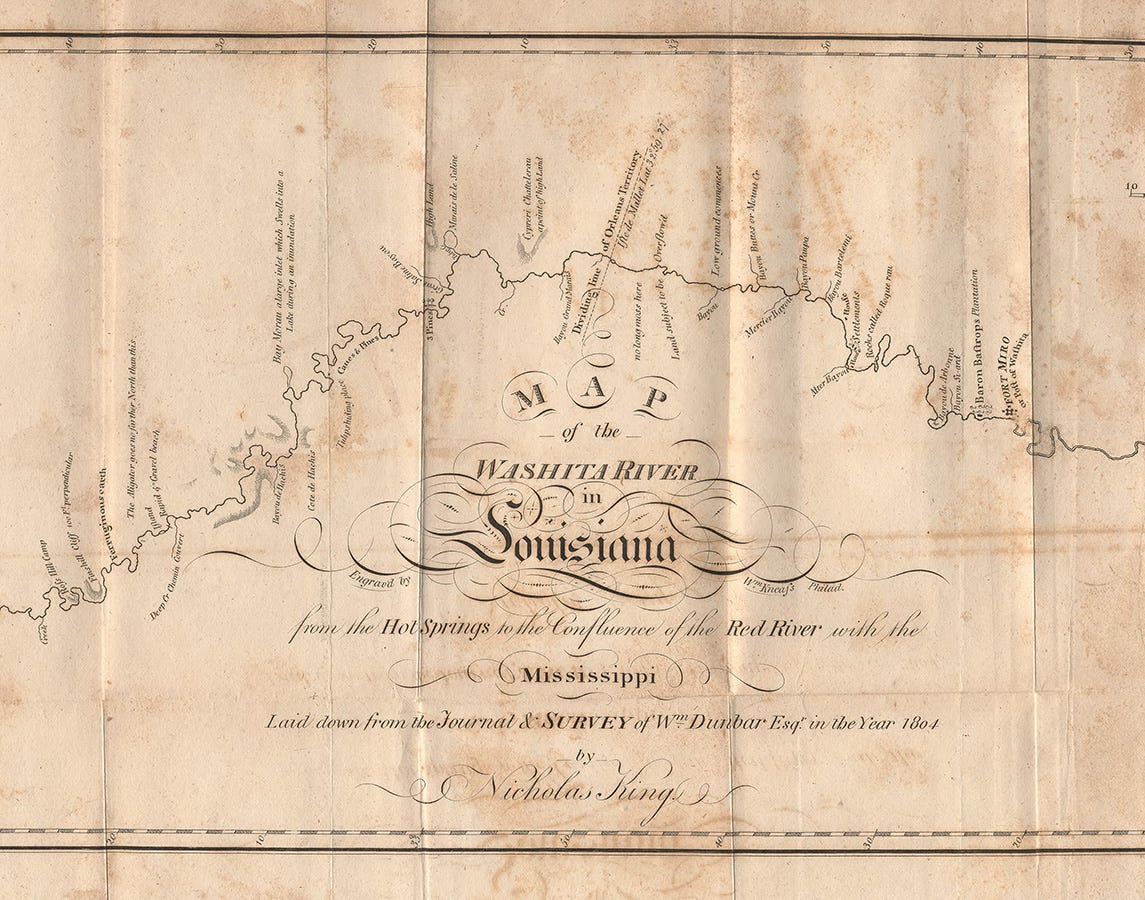

His partner was Dr. George Hunter, a practical, no-nonsense chemist and druggist from Philadelphia with significant frontier experience. One was an aristocratic intellectual, the other a hands-on pragmatist. Together, they were tasked with a singular objective: to push their way up the treacherous Ouachita River and conduct the first-ever scientific investigation of the fabled “hot waters of the Washita.” They were about to become the first scientists to truly study the mystery at the heart of Hot Springs.

A Grand Plan for a Grand Purchase

To understand why this expedition happened, you have to get inside Thomas Jefferson’s head. It’s 1803, and the man just pulled off the real estate deal of the millennium, buying half a billion acres from Napoleon, sight unseen. For Jefferson, this wasn’t just about territory; it was about knowledge. Long before the ink on the Louisiana Purchase treaty was dry, he was already scheming about how to explore, catalog, and ultimately control the continent. For Jefferson, to know the land was to own the land, and exploration was the primary means of acquiring that knowledge.

So, while Lewis & Clark were getting ready to tackle the northern half of the purchase by tracing the Missouri River, Jefferson set in motion a southern counterpart: the “Grand Expedition.” And let me tell you, the original plan was staggering in its ambition.

The idea wasn’t to just take a quick peek up some backwater river. Jefferson’s instructions charged Dunbar and Hunter with ascending the Red River deep into territory claimed by Spain, finding its source, crossing a short (and entirely theoretical) portage to the headwaters of the Arkansas River, and then descending the Arkansas all the way back to the Mississippi. If successful, the journey would have been every bit as epic as the one being undertaken by the Corps of Discovery.

This route was a calculated geopolitical chess move. It was strategically designed to probe the sensitive and poorly defined southwestern border with New Spain, gather intelligence on a vast and contested region, and plant an American flag - figuratively speaking - in areas coveted by European rivals. But as anyone who’s ever tried to plan a road trip knows, the map is never the territory. And the territory Dunbar and Hunter were about to enter had other plans.

Dodging Spaniards & the Osage

Jefferson’s “Grand Expedition” was a brilliant plan on paper, but it had two big, frontier-sized problems. First, there were credible reports of hostility from the powerful Osage tribes who controlled the territory along the proposed Arkansas River route. Jefferson himself wrote to Dunbar expressing grave concern that the Osage would “hinder their travel… and perhaps do worse.” The Osage had made it pretty clear that uninvited American survey parties wouldn’t be welcome.

Second, and perhaps even more dicey, was the very high probability that Spanish authorities would intercept and arrest the expedition. The Spanish government didn’t fully recognize the extent of the Louisiana Purchase and was deeply suspicious of American encroachment on the borderlands of New Spain. Sending an official US government party up the Red River was like waving a red flag at a very angry bull. The grand design was ultimately scuttled by this sober intelligence from the frontier.

This is where William Dunbar proved he was the right man for the job. Rather than pack it in, Dunbar, the knowledgeable man on the ground, proactively wrote to Jefferson on August 18, 1804. He proposed an alternative: a smaller, safer, but still scientifically valuable “Excursion up the Washita River and to the hot springs.” He astutely framed it as a “trial run” that could be undertaken immediately, avoiding the dangers of the original route while still gathering crucial data on the new territory.

Jefferson, a pragmatist above all else, agreed. And just like that, the high-risk geopolitical probe was transformed into a focused scientific survey. The mission was no longer about rivaling Lewis & Clark in scope, but about producing the first hard data from the southern frontier - a journey that would take them up the winding Ouachita to the legendary “boiling springs”.

19 Men, 1 Terrible Boat, and a Mind-Blowing Discovery

The Grueling Journey Upriver

The newly christened Ouachita Expedition launched from St. Catherine’s Landing, near Natchez, on October 16, 1804. The party was a perfect snapshot of the early republic: Dunbar and Hunter, the two scientific leaders; a military escort of 13 US Army soldiers; Hunter’s teenage son; and, critically, one of Dunbar’s servants and two of his enslaved men, a stark reminder that even federal missions of discovery were entangled with the institution of slavery.

From the very beginning, the journey was a masterclass in misery, starting with their main ride. Dr. Hunter had designed a vessel he described as being built in the “Chinese stile [sig],” which proved to be a complete and utter disaster for river travel. Its draft was far too deep, causing it to snag on the shallow river bottom constantly. Dunbar’s frustration is palpable in his letters to Jefferson, where he lamented that the boat was an “unprofitable Vessel” that demoralized the crew, who constantly had to wade into the cold water to push it off sandbars. The thing was such a lemon that they were forced to abandon it at Fort Miro (modern-day Monroe, Louisiana) and hire a much more suitable shallow-draft flatboat, a move that likely saved the mission from total failure.

As if the boat wasn’t bad enough, on November 22, Dr. Hunter provided the trip’s most dramatic moment of personal peril. While cleaning his pistol, it slipped and discharged, tearing through his thumb and two fingers. The blast scorched his skin, burned off his eyebrows, and passed less than an inch from his temple. It was a near-fatal accident that left him in severe pain and unable to even write in his journal for over two weeks; the entries for that period had to be copied from Dunbar’s log after the fact. Mere days later, the entire crew had to summon every ounce of strength to navigate “the Chutes,” a formidable, mile-long series of rocky rapids near modern-day Malvern that Dunbar said roared like a hurricane he had experienced years before.

Finally, on December 7, 1804, after nearly two months of toil, the exhausted party arrived at the confluence of the Ouachita River and Calfait Creek (now known as Gulpha Creek), the closest navigable point to the hot springs. After a grueling journey, they had reached the fabled Valley of Vapors. It was time to see what all the fuss was about.

First Impression: A Frontier Health Spa

After setting up a base camp at the river, a small party pushed the last few miles overland to the springs on December 9, 1804. They were likely expecting to find a pristine, untouched natural wonder. Instead, they stumbled upon what could only be described as a crude, backcountry health spa.

Waiting for them was “an Open Log-Cabin and a few huts of split boards… for summer encampment… erected by persons resorting to the Springs for the recovery of their health…”. The secret of the Valley of Vapors was already out. For years, American settlers and frontiersmen had been making pilgrimages to this spot. Dunbar and Hunter had walked into a well-known, if rustic, sanatorium.

This was the scene - a functioning, if primitive, health resort. Realizing its value as a shelter, the explorers made the crude log cabin their base camp and prepared to turn the frontier spa into the first scientific field station in Arkansas history.

While the expedition’s scientific journals don’t detail the specific bathing methods they witnessed, accounts from visitors just a couple of decades later paint a vivid picture of what this primitive spa was like. The “bathing regimen” was about as basic as it gets. According to a history of the park, normal bathing facilities around 1830 were “mere cavities cut in the tufa rock, into which the water ran, serving as tubs, with a screen of bushes lending an inadequate touch of privacy.”

The steam baths were even more rustic. The “first vapor bath facility was a niche cut into the tufa rock… covered overhead with rocks and boards, and in front with a blanket.” A visitor in 1835, George Engelmann, confirmed this, describing three steam baths set up under a rock overhang where “the hot vapors rise up and envelop anyone sitting on the benches.”

With their camp established and an understanding of how the springs were being used, it was time for the real work to begin. For nearly a month, Dunbar and Hunter dedicated themselves to a rigorous scientific investigation, aiming to replace folklore and rumor with empirical facts.

The Scientific Mission

For nearly a month, from early December 1804 into January 1805, the explorers transformed the rustic camp into Arkansas’s first scientific field station. Their work was systematic and rigorous. They conducted the first known scientific analyses of the thermal waters, using a Fahrenheit thermometer to record temperatures ranging from 130°F to 150°F. Dr. Hunter’s chemical tests were remarkably insightful for the time. He determined that the water wasn’t unusually high in minerals, but that its most notable characteristic was the deposit of what Dunbar called an “immense body of Calcareous matter” - the calcium carbonate rock we know as tufa - which coated the entire hillside.

They cataloged the local geology, noting the prevalence of novaculite, a hard, flint-like rock ideal for making whetstones. Dunbvar, the meticulous naturalist, even discovered and described a new plant species he named the “cabbage raddish of the Washita.” But the expedition’s most profound and forward-looking discovery came from Dunbar peering through a microscope.

In water he measured at 130°F, Dunbar observed what he called “Vegetable and animal life.” He described seeing a “species of moss,” now understood to be a type of thermophilic blue-green algae, and a “testaceous bivalve of the size of the minutest grain of Sand,” which was a microscopic shelled animal. This stands as arguably the first documented report of living organisms thriving in such a high-temperature, seemingly hostile environment in North America. While Dunbar and Hunter couldn’t have grasped the full biological significance of these “extremophiles,” their meticulous recording of the phenomenon represents a foundational moment in a field of study that would not formally emerge for more than a century. It elevates their work from mere cataloging to an instance of true, paradigm-shifting scientific discovery.

A Forgotten Triumph

Having completed their scientific work, the party broke camp on January 8, 1805, and began the much faster journey downstream. The full expedition concluded on January 26, when the remaining party, under Dr. Hunter, returned to the Natchez area, officially ending the 103-day journey. Their mission was a resounding success, and its most immediate impact was felt in the nation’s capital.

Their detailed journals were the first official report from any of the Louisiana Purchase explorations to reach President Jefferson, providing his administration with its initial scientific glimpse into the new territory. Dunbar’s findings arrived on the president’s desk more than a year before Lewis & Clark returned from their trip to the northwest. On February 19, 1806, Jefferson formally presented their discoveries to the US Congress, cementing the expedition’s official success.

So, if they were first in the field and first to report, why aren’t Dunbar and Hunter household names? The simple, slightly frustrating answer is that their story lacked narrative grandeur. The Lewis & Clark expedition was a transcontinental epic, a 2 1/2-year odyssey to the Pacific Ocean and back that has become a national founding myth. The Dunbar-Hunter expedition, by contrast, was a shorter, regional, and intensely technical survey. Its primary output wasn’t a thrilling adventure narrative but a dense scientific report filled with astronomical tables and chemical analyses, intended for an audience of one: President Jefferson. National memory is built on compelling stories, not on raw data, and their journey was ultimately “forgotten” because its form—a rigorous scientific paper—was less accessible to the popular imagination than the epic poem of the Lewis & Clark saga.

Despite being overshadowed, their work had a profound and lasting impact. It provided the first accurate, scientific understanding of the unique geology and resources of the Ouachita region, officially putting the hot springs on the national map. It was this foundational knowledge that laid the groundwork for the federal government to protect the area, establishing the Hot Springs Reservation just a few decades later in 1832.

Why the “Other” Expedition Matters

So, was the Dunbar-Hunter expedition a failure because it never reached the headwaters of the Red River? Absolutely not. When judged on its actual mission, it was a profound success. It was a story of pragmatic adaptation in the face of frontier realities, a triumph of Enlightenment science, and a critical first step in the nation’s understanding of its vast new territory.

Their journey up the Ouachita provided the United States with its first official, scientific report on the Louisiana Purchase, and their meticulous work gave the world its first real look at the unique geology and biology of the Valley of Vapors. While Lewis & Clark were writing an epic poem of adventure, Dunbar and Hunter were composing a rigorous scientific encyclopedia—a document that, although less famous, was instrumental in putting Hot Springs on the national map and led directly to its protection as a federal reservation. Their forgotten expedition wasn’t just a trip to some hot water in the woods; it was the scientific birth of Hot Springs.

If you enjoyed this deep dive into Hot Springs' foundational history, share it with a fellow history buff! And for more stories from the archives, consider upgrading to a paid subscription.

References

Benson, F. M., & Libbey, D. S. (n.d.). History of Hot Springs National Park. National Park Service.

Berry, T., Beasley, P., & Clements, J. (Eds.). (2006). The forgotten expedition, 1804-1805: The Louisiana Purchase journals of Dunbar and Hunter. LSU Press.

DeRosier, A. H., Jr. (n.d.). William Dunbar: Scientific pioneer of the Old Southwest. University Press of Kentucky.

Dunbar, W. (1804, August 18). To Thomas Jefferson from William Dunbar, 18 August 1804. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-44-02-0241

Dunbar, W. (1804, November 9). William Dunbar to Thomas Jefferson, November 9, 1804. The Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress. http://jeffersonswest.unl.edu/archive/view_doc.php?id=jef.00010

Dunbar, W. (1805, February 15). To Thomas Jefferson from William Dunbar, 15 February 1805. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-45-02-0514

Foley, L. (Producer & Writer), & Carpenter, D. (Director). (2002). The Forgotten Expedition [Film]. University of Arkansas; AETN; Ouachita Baptist University.

Garland County. (n.d.). Garland County history. Retrieved July 23, 2025, from https://www.garlandcounty.org/308/Garland-County-History

Hot Springs Guest Guide. (2020, February 17). The history of Hot Springs. https://www.hsguestguide.com/post/102652/hot-springs-history

Hunter, G. (1803, August 2). From George Hunter, 2 August 1803. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-41-02-0100

Jefferson, T. (1804, April 15). From Thomas Jefferson to William Dunbar, 15 April 1804. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-43-02-0209

Jefferson's "Other" Expedition: The forgotten explorers of Hot Springs. (n.d.). [Unpublished research report].

McDermott, J. F. (Ed.). (1963). The Western journals of Dr. George Hunter, 1796-1805. American Philosophical Society.

McMichael, A. (n.d.). William Dunbar. In Mississippi Encyclopedia. Retrieved July 23, 2025, from https://mississippiencyclopedia.org/entries/william-dunbar/

Monticello. (n.d.-a). Exploration. Thomas Jefferson's Monticello. Retrieved July 23, 2025, from https://www.monticello.org/thomas-jefferson/thomas-jefferson-and/exploration/

Monticello. (n.d.-b). William Dunbar. Thomas Jefferson's Monticello. Retrieved July 23, 2025, from https://www.monticello.org/research-education/thomas-jefferson-encyclopedia/william-dunbar/

National Park Service. (n.d.). The forgotten expedition of Dunbar and Hunter. U.S. Department of the Interior. https://npshistory.com/publications/hosp/brochures/dunbar-hunter.pdf

National Park Service. (2024). When did it happen? A chronology of historic events at Hot Springs National Park.

Sabo, G., III. (2024, March 12). Garland County. In Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved July 23, 2025, from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/garland-county-770/

Sabo, G., III. (2024, March 12). Hunter-Dunbar expedition. In Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved July 23, 2025, from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/hunter-dunbar-expedition-2205/

United States. President (1801-1809: Jefferson). (1806, February 19). Message from the President of the United States, communicating discoveries made in exploring the Missouri, Red River, and Washita, by Captains Lewis and Clark, Doctor Sibley, and Mr. Dunbar.

Weddle, B. (2007). The Forgotten Expedition, 1804-1805: The Louisiana Purchase Journals of Dunbar and Hunter [Review of the book The Forgotten Expedition, 1804-1805: The Louisiana Purchase Journals of Dunbar and Hunter, by T. Berry, P. Beasley, & J. Clements, Eds.]. Southwestern Historical Quarterly, 111(1), 117-118. https://doi.org/10.1353/swh.2007.0080