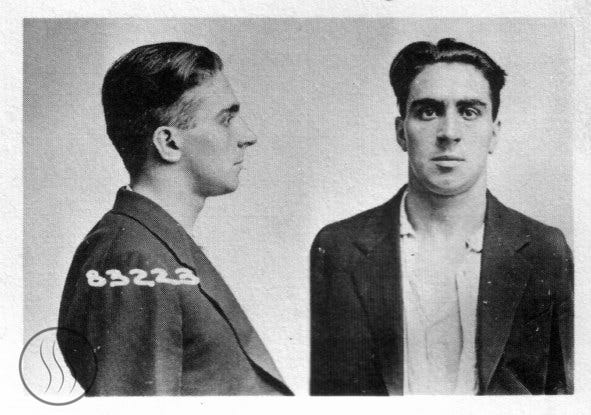

In the winter of 1927, Al Capone was the undisputed, blood-soaked king of Chicago. He commanded a private army, controlled a vast criminal empire netting an estimated $105 million annually, and was waging a brutal war against his North Side rivals that left dozens dead in the streets. He was, by any measure, one of the most powerful and dangerous men in America.

And he needed a vacation.

For a man like Capone, a vacation wasn’t just a matter of leisure; it was a strategic necessity. He needed a place to escape the constant threat of assassination, the prying eyes of federal agents, and the frigid chill of a Chicago winter. He needed a sanctuary. He found it in an unlikely place: a quiet, picturesque resort town nestled in the Ouachita Mountains of Arkansas.

The American Spa: A Gangster’s Neutral Ground

Long before Capone’s arrival, Hot Springs had cultivated a dual identity. By day, it was the “American Spa,” a world-renowned health resort where visitors flocked to “take the waters,” believing the 143-degree thermal springs possessed miraculous healing properties. By night, however, it transformed into “The Devil’s Town,” a wide-open haven of illegal gambling, bootleg liquor, and prostitution, all operating with the blessing of a sophisticated and deeply corrupt local political machine.

This unique environment made it the perfect neutral ground for the American underworld. An unwritten rule existed among the visiting mobsters: leave your wars at the city limits.

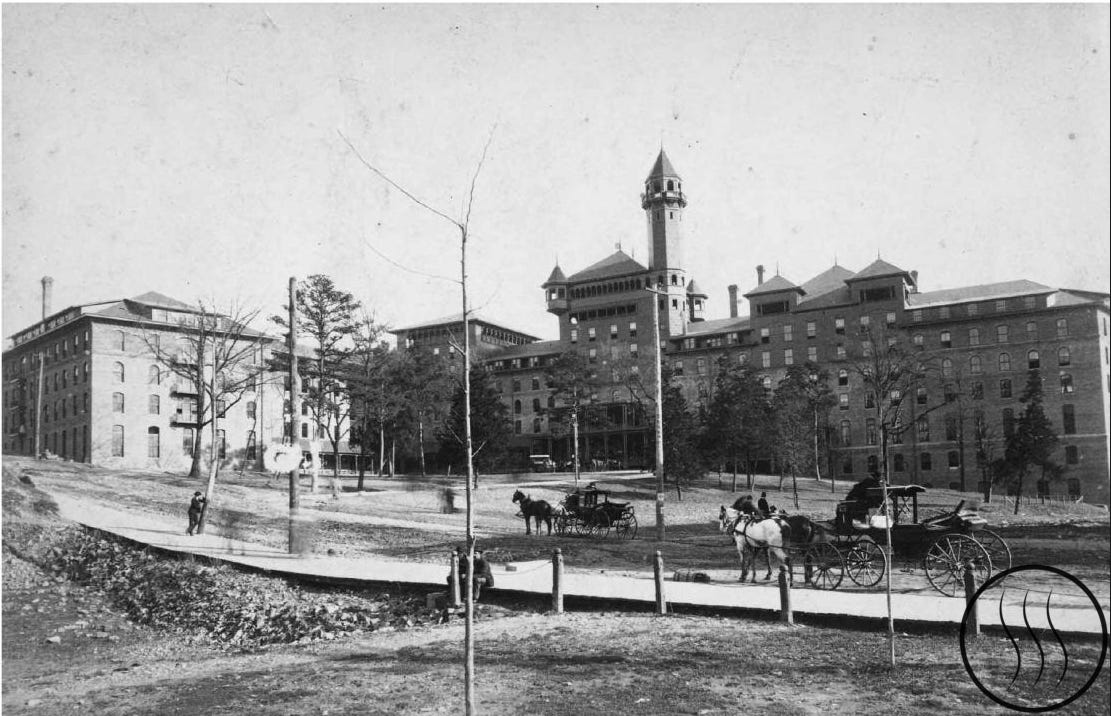

Capone was first introduced to this paradise of plausible deniability by his mentor, the shrewd Chicago mob boss Johnny Torrio, who brought him on a trip likely in the fall of 1920. Torrio, who preferred a lower profile, chose the elegant Eastman Hotel as their base of operations. For a time, it worked well. But Capone’s crew, even in their early days, had a certain flair for chaos. After one particularly “raucous party,” the management of the Eastman politely suggested that the boys from Chicago might be more comfortable somewhere else. This “invitation to leave” was a pivotal moment. The newly opened Arlington Hotel, even more grand and opulent, was just across the way, ready and willing to cater to a new class of high-rolling clientele, no matter where their money came from.

Suite 443: A Fortress with a View

Once Capone took over the Chicago Outfit from Torrio in 1925, the Arlington became his official southern headquarters. He favored Suite 443, a corner suite with a commanding view of Central Avenue. It was more than just a room; it was a fortress with a view. From his window, he had a clear line of sight to the Southern Club, one of the premier gambling joints in town, and could watch the world go by.

This was no mere hotel room; it was his southern command center. On his larger trips, Capone was known to rent out the entire fourth floor to house his army of bodyguards, cooks, and associates, ensuring total privacy and security. The local police were not a concern; a “contribution” to the Policeman’s Benevolent Fund and a courtesy call to Mayor Leo McLaughlin’s office ensured the Chicago boys would be left alone. Capone was free to focus on his health, a persistent case of syphilis that he hoped the town’s famous thermal waters could cure.

A Gangster’s Holiday: Golf, Gambling, and Good Times

Freed from the pressures of Chicago, Capone embraced the life of a wealthy tourist. He was a fixture at Oaklawn Park during the horse racing season, where he was known to wager up to $100,000 on a single race. He and his top lieutenants, like “Machine Gun” Jack McGurn and “Greasy Thumb” Guzik, were regulars at the Hot Springs Country Club. However, their golf skills were reportedly less impressive than their arsenal, with pistols often hidden in their golf bags.

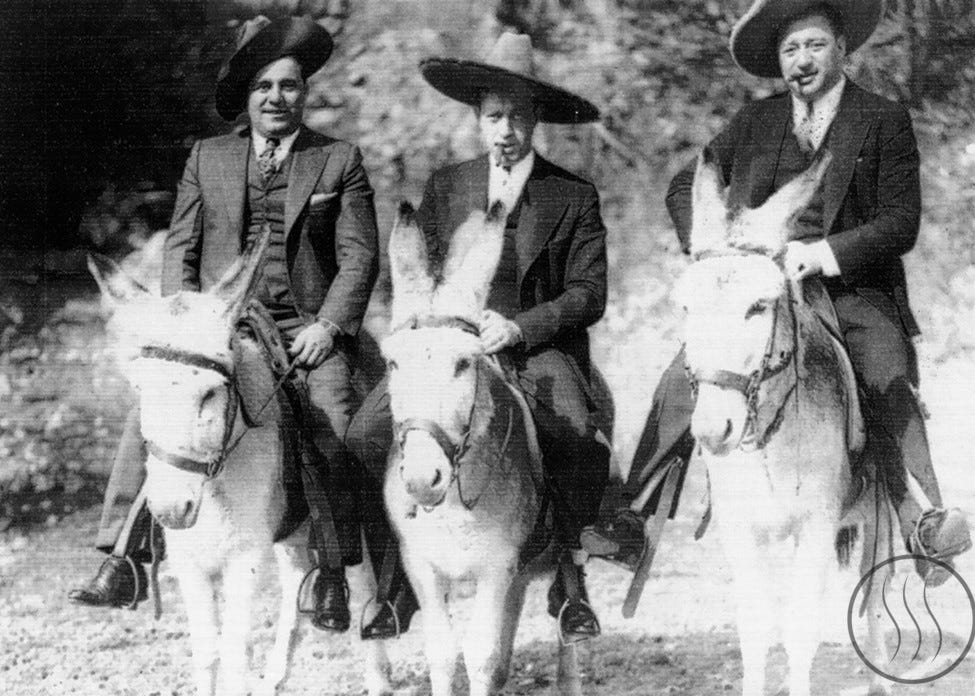

He gambled heavily at the local casinos, particularly the Southern Club, run by the city’s “Boss Gambler,” W.S. Jacobs. An infamous local story recounts Capone storming out of the club after a losing streak, leaving thousands in markers unpaid, only to have his brother Ralph quietly settle the debt later, knowing they couldn’t afford to alienate the local management. He could even be seen at tourist traps like the Happy Hollow Amusement Park, posing for silly photos on the back of a burro - a surreal image of a man responsible for hundreds of deaths back in Illinois.

When the War Followed Him South

Despite the town’s “neutral” status, the violence of Chicago couldn’t always be kept at bay. In March of 1927, Capone’s top North Side rival, Vincent “Schemer” Drucci, followed him to the Spa City with the clear intent of assassination. According to one account, Drucci and his men spotted Capone driving a roadster on Park Avenue and sprayed the car with gunfire. Capone, “fat but quick,” allegedly hit the brakes and tumbled out of the moving vehicle into a ditch, escaping unharmed as his car crashed into a tree. The incident was never reported to the local police - it was a Chicago problem, and Capone would deal with it later. (Drucci was killed by a Chicago detective just one week after his return from Chicago.)

An Enduring Legacy

For nearly a decade, Al Capone’s presence was an open secret in Hot Springs. He was the city’s most famous and feared health seeker. His regular visits cemented the town’s national reputation as a place where the powerful and the profane could relax side-by-side, where the healing waters of the Valley of Vapors washed away sins and sorrows, at least temporarily. For a price, anyone could find sanctuary here, even Public Enemy Number One.

References

Al Capone in Hot Springs, 1924–1930_ A foundational report on archival sources and historical context. (2025).

Allbritton, O. E. (2011). The mob at the spa: Organized Crime and Its Fascination with Hot Springs, Arkansas.

Kobler, J. (2003). Capone: The Life and World of Al Capone. Da Capo Press.

Leigh, P. (2018). The Devil’s Town: Hot Springs During the Gangster Era.

Nash, J. R. (2004). The great pictorial history of world crime. Scarecrow Press.

Hanley, R. (2011). A place apart: A Pictorial History of Hot Springs, Arkansas. University of Arkansas Press.

Benson, F. M., & Libby, D. S. (n.d.). History of Hot Springs National Park. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/hosp/hot_springs_history.pdf

Hot Springs Guest Guide. (2020, February 17). The History of Hot Springs. Retrieved from https://www.hsguestguide.com/post/102652/hot-springs-history