How to Build a Spa Town: A Hot Springs Tale of Fire, Floods, and Furious Egos

The only thing hotter than the water in 19th-century Hot Springs were the fires that kept burning the town down. Here's how they finally built something that would last.

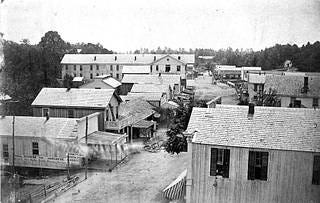

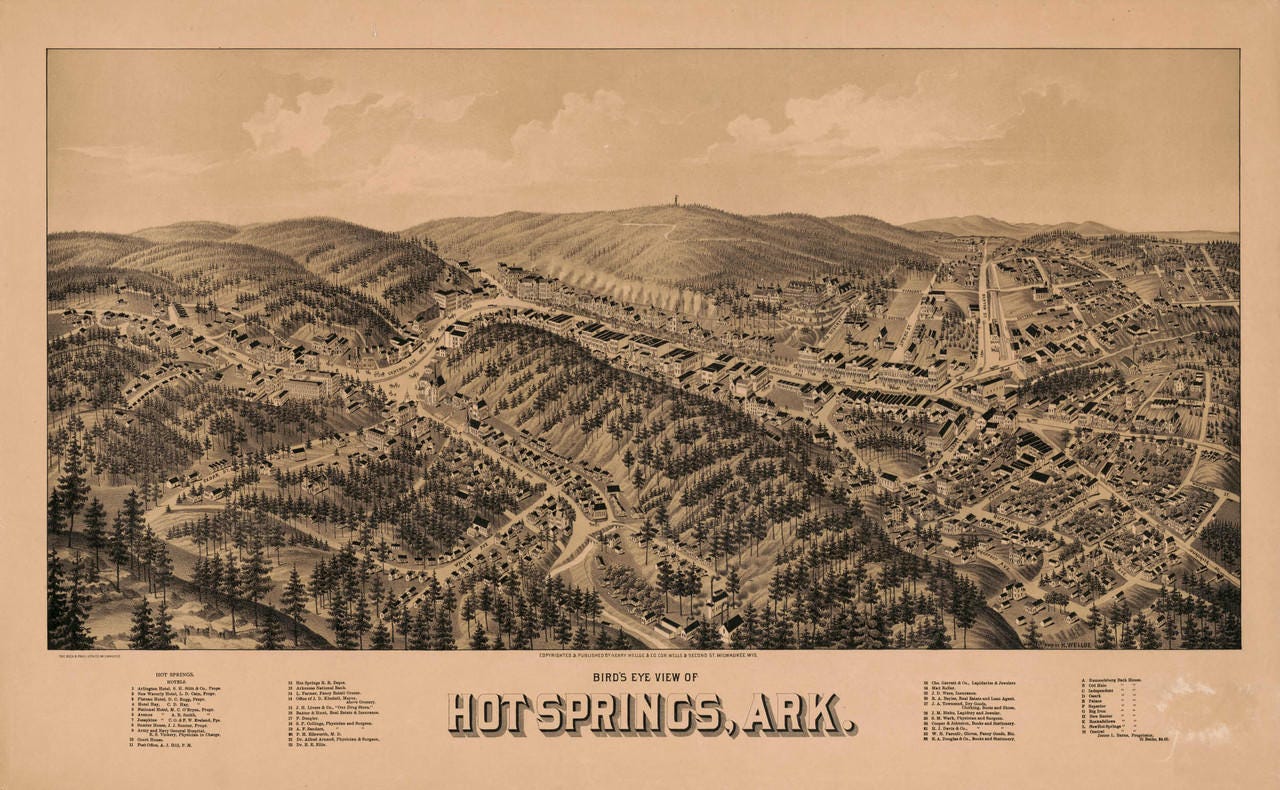

For a place that built its international reputation on healing the sick, 19th-century Hot Springs was a remarkably hazardous place to visit. The marketing was brilliant, of course. Railroads and guidebooks breathlessly promoted the “Valley of Vapors” as a miracle cure for everything from rheumatism to alcoholism, drawing in thousands of hopeful invalids. The reality on the ground, however, was slightly less glamorous. To get to the healing waters, you first had to navigate a ramshackle frontier town built around what was, politely speaking, an open sewer.

This wasn’t some picturesque mountain stream. Hot Springs Creek, which ran right through the main thoroughfare, served as the town’s primary drain for everything. It was a polluted, flood-prone ditch that visitors had to cross on rickety footbridges. If the sanitation didn’t get you, the architecture might. The town’s hotels and bathhouses were almost entirely wooden tinderboxes, constantly rotting from the thermal steam or, more spectacularly, burning to the ground. The local specialty wasn’t just hydrotherapy; it was impromptu urban renewal by inferno.

It was, to be blunt, a mess. And it’s this foundational absurdity - a world-class health resort that was both unsanitary and uninsurable - that makes the story of Bathhouse Row so incredible. The magnificent, fireproof palaces we see today weren’t born from a single, enlightened vision. They were forged out of necessity, the result of a decades-long struggle to finally solve the town’s most glaring, flammable, and foul-smelling problems.

An Uninsurable Paradise

The first commercial bathhouses built in Hot Springs were exercises in misplaced optimism. After graduating from simple log cabins and canvas tents perched precariously over springs, entrepreneurs in the 1850s began erecting larger, wooden-framed structures, often decorated with the Victorian gingerbread popular at the time. They were handsome, hopeful, and fundamentally doomed. Building a town entirely out of wood in a valley that was perpetually hot and steamy presented two significant, and ultimately unavoidable, problems.

First, there was the rot. The constant thermal vapor was hell on timber. An investigator in the 1890s, looking back at the era, stated flatly that the steam “rots all timber with which it comes in contact in remarkably short time.” It was an insidious, silent process that weakened buildings from the inside out. If the rot didn’t claim a building, fire almost certainly would. In a town where every structure was essentially a well-seasoned tinderbox, it wasn’t a question of if the town would burn, but when and how spectacularly.

The inevitable finally happened on a massive scale in March 1878. The “Great Fire” ripped through the heart of the city, and in just eight hours, some 150 buildings - including most of the bathhouses and hotels - were gone. It was a catastrophic financial loss, but it was also the best thing that could have happened to Hot Springs. The blaze was a brutally effective form of urban renewal, wiping the slate clean of the flammable, ramshackle structures. This predictable disaster created the undeniable mandate - and the physical space - for a complete and fireproof reimagining of the bathing district, forcing everyone to finally build something that might actually last.

The Government Gets Its Act Together (Finally)

It often takes a truly spectacular disaster to get a bureaucracy moving, and the Great Fire of 1878 was nothing if not spectacular. The federal government had technically owned the Hot Springs Reservation since President Andrew Jackson signed a bill in 1832; however, for over 40 years, Congress had largely ignored it, allowing a chaotic mass of land claims and lawsuits to fester. It wasn’t until 1876 that the US Supreme Court finally put an end to the squabbling and affirmed federal control. The very next year, the first superintendent was appointed to bring order to the valley. Then, almost on cue, the town burned down. With the ground conveniently cleared and its authority now undisputed, the government could finally start acting like a landlord.

The first order of business was monumental. To build a proper resort, they had to eliminate the town’s most disgusting feature: Hot Springs Creek. So, between 1882 and 1884, in a Herculean feat of 19th-century engineering, the entire polluted, flood-prone waterway was enclosed in a massive subterranean arch of stone and brick. The project was a brilliant two-for-one deal. It permanently solved the sanitation and flooding problems while simultaneously creating a wide, stable, and valuable piece of real estate where none had existed before. The creek was buried, covered with earth, and landscaped into a pleasant park, creating the literal foundation for the modern Bathhouse Row.

With the land problem solved, the government then consolidated its power by seizing total control of the water itself. By 1901, all 47 thermal springs were walled up and protected, with their flow funneled into a new, centralized system of underground pipes. This was the masterstroke. By controlling both the ground leases and the water spigots, the Department of the Interior became the ultimate authority. They could finally enforce strict, non-negotiable rules for anyone wanting to do business, chief among them being a simple, hard-learned mandate: no more wooden buildings. The era of the tinderbox was over; anything new had to be fireproof. The stage was now perfectly set for a new kind of chaos: the architectural arms race.

Keeping Up with the Maurices

On Bathhouse Row in the early 20th century, it wasn’t about keeping up with the Joneses; it was about keeping up with the Maurices. With the federal government providing a stable, fireproof foundation, the private proprietors leasing the lots engaged in a furious, decade-long contest of one-upmanship. This wasn’t a collaboration; it was an all-out architectural war fought with marble, stained glass, and enormous egos.

The opening shots were fired in 1912. In January, William “Billy” Maurice opened his new Maurice Bathhouse, a sophisticated Mediterranean-style palace that immediately set a new standard for luxury. It was the first built under new, stricter federal mandates for advanced equipment and ventilation, and it was designed to attract the wealthiest clientele. A month later, the stately, Neoclassical Buckstaff opened right next door, a formal and imposing competitor. The game had officially changed. The old wooden Victorian structures that remained now looked hopelessly obsolete.

Watching all of this was Colonel Samuel W. Fordyce, a railroad magnate who had no intention of being outdone. In a legendary act of competitive spite, Fordyce deliberately waited to build his bathhouse so he could first see what the Maurice offered, ensuring he could create a “more attractive and convenient” facility. When the Fordyce opened in 1915, it was a mic drop in brick and marble. Costing over $212,000, it was the largest and most opulent bathhouse on the Row, a masterpiece of Renaissance Revival design featuring walls of Italian marble, a massive stained-glass skylight, a bowling alley, and the largest gymnasium in the state. The arms race was over, and Fordyce had won.

But the competition wasn’t just for the high rollers. Other proprietors cleverly targeted different segments of the market. The Superior, opened in 1916, was the smallest and least expensive bathhouse, competing on service and affordability rather than opulence. The Ozark (1922) also went after the middle-class bather; its owners famously rejected three earlier, more expensive architectural plans before settling on the final design. The Ozark, along with the visually stunning, dome-topped Quapaw (1922), also offered a key competitive advantage: all their bathing facilities were on the first floor, a practical draw for the many elderly and handicapped patrons who couldn’t easily navigate the multi-story palaces of their rivals.

The Gilded Cage & Its Afterlife

When the Lamar Bathhouse opened its doors in 1923, the great construction boom was officially over. The architectural arms race had produced a stunning, eclectic set of eight masonry palaces that stood in proud, fireproof defiance of the town’s chaotic past. But the furious, competitive energy that built the Row had run its course. For the next few decades, the eight bathhouses settled into their roles, serving a steady stream of visitors. And then, the world changed.

Starting in the 1940s and accelerating after World War II, modern medicine began to do what Hot Springs’s thermal water had only ever promised. With the advent of penicillin and other antibiotics, the belief in the healing water faded. The bathing industry entered a long, slow decline. The first major blow came in 1962, when the magnificent Fordyce - the undisputed king of the Row - closed its doors for good. The others followed over the next two decades: the Maurice in 1974, the Ozark in 1977, the Hale in 1978, and the Superior, Quapaw, and Lamar in the mid-1980s. By 1985, only the stalwart Buckstaff remained, a lone survivor of a bygone era.

Ironically, the death of the industry is precisely what saved the buildings. The greatest threat to a historic structure is often a booming economy, which provides the incentive to tear down the old to make way for the new. But in Hot Springs, the bathing economy went bust. There was no money and no reason to demolish these grand, obsolete bathhouses. They sat, becoming a perfect architectural snapshot of the Progressive Era, preserved by economic stagnation. They became a gilded cage - beautiful, ornate, and empty.

This period of neglect eventually gave way to a new era of appreciation. In 1974, Bathhouse Row was placed on the National Register of Historic Places, sparking a civic campaign to find new, adaptive uses for the vacant buildings. The first major success was the meticulous restoration of the Fordyce, which reopened in 1989 as the National Park’s visitor center and museum. In the decades since, others have followed, finding a vibrant afterlife that the original builders could never have imagined. Today, you can stay overnight in the luxurious Hotel Hale, enjoy a modern spa experience at the Quapaw, or drink a beer brewed with thermal water at the Superior Bathhouse Brewery - a lasting, and evolving, legacy for an uninsurable paradise.

More Than Just Marble and Mortar

When you look at Bathhouse Row today, you see a masterpiece of historic preservation. But the real story isn’t about a plan; it’s about a perfect storm of chaos and ambition. This magnificent architectural collection wasn’t born from careful civic foresight. It was the accidental, glorious result of three key ingredients: catastrophic fires that repeatedly wiped the slate clean, belated and heavy-handed government intervention that created the very ground it sits on, and the furious, ego-driven competition of Gilded Age capitalists trying to build the largest and most impressive toy on the block.

It’s a quintessential American story. We built our most beautiful and enduring monument to health on a foundation of disaster, bureaucratic muscle, and a high-stakes commercial rivalry. The great irony is that these palaces, built for all the wrong reasons, have outlasted the industry they were meant to serve, surviving to tell a fascinating tale about a truly special, and wonderfully weird, chapter in the history of Hot Springs.

References

Brittenum, J. B. (2013). What war has joined together: Samuel W. Fordyce's war experiences influence the establishment of the Hot Springs Army and Navy General Hospital. The Record, 44, 5.1–5.10.

Hanley, R. (2011). A place apart: A pictorial history of Hot Springs, Arkansas. University of Arkansas Press.

Hanley, R., & Hanley, S. (2000). Hot Springs, Arkansas. Arcadia Publishing.

Hill, T., Hanks, A., Shugart, S., Hill, M. B., Padron, J., Sanderson, J., Baker, C., & Young-Dahl, E. (2024). When did it happen? A chronology of historic events at Hot Springs National Park. National Park Service.

National Park Service. (n.d.-a). Architecture in the parks (Bathhouse Row). U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/harrison/harrison2.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.-b). Bathhouse Row. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/bathhouse-row.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.-c). Bathhouse Row cultural landscape. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/articles/500341.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.-d). Bathhouse Row today. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/bathhouse-row-today.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.-e). Benjamin F. Kelley. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/benjamin-f-kelley.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.-f). Buckstaff Bathhouse. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/buckstaff-bathhouse.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.-g). Fordyce Bathhouse. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/fordyce-bathhouse.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.-h). Hale Bathhouse. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/hale-bathhouse.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.-i). Lamar Bathhouse. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/lamar-bathhouse.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.-j). Maurice Bathhouse. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/maurice-bathhouse.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.-k). Ozark Bathhouse. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/ozark-bathhouse.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.-l). Return of the Quapaw Bathhouse. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/planyourvisit/return-of-the-quapaw-bathhouse.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.-m). Samuel Fordyce. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/samuel-fordyce.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.-n). Superior Bathhouse. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/places/superior-bathhouse.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.-o). Uncovering Ral City. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/uncovering-ral-city.htm

Paige, J. C., & Harrison, L. S. (1987). Out of the vapors: A social and architectural history of Bathhouse Row. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. https://npshistory.com/publications/hosp/out-of-the-vapors.pdf

Rains, G. (2011). George Richard Mann (1856–1939). In Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Central Arkansas Library System. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/george-richard-mann-2117/

Richter, W. L. (2022). Hot Springs (Garland County). In Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Central Arkansas Library System. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/hot-springs-887/

Richter, W. L. (2023). Bathhouse Row. In Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Central Arkansas Library System. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/bathhouse-row-437/

Scaife, T. (2022). Samuel Wesley Fordyce (1840–1919). In Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Central Arkansas Library System. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/samuel-wesley-fordyce-1649/

Scully, F. J. (2013). Hot Springs National Park. In Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Central Arkansas Library System. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/hot-springs-national-park-2547/

U.S. Department of the Interior. (1914). Annual report of the superintendent of the Hot Springs Reservation to the Secretary of the Interior for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1914. Government Printing Office. https://npshistory.com/publications/annual_reports/hosp/1914.htm

U.S. Department of the Interior. (1920). Rules and regulations, Hot Springs National Park. Government Printing Office. https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/brochures/1920/hosp/sec2.htm