In the spring of 1802, a shadow was stretching across the American West. From his desk in Washington, President Thomas Jefferson watched with alarm as reports confirmed his fears: the vast territory of Louisiana was being transferred from the feeble hands of Spain to the formidable grasp of Napoleonic France. From the young United States, this was a crisis of the first order. The port of New Orleans - the indispensable outlet for the entire Mississippi River basin - was about to be controlled by the most powerful and ambitious ruler in Europe.

“Every eye in the US is now fixed on this affair of Louisiana,” Jefferson wrote in a letter, noting that “perhaps nothing since the revolutionary war has produced more uneasy sensations through the body of the nation.” He predicted a “tornado” that would burst upon the shores of the Atlantic.

But the key to this American storm, the unpredictable event that would ultimately decide the fate of lands as distant as Hot Springs, Arkansas, was not taking place in the diplomatic halls of Washington or Paris. It was igniting in the brutal, sugar-rich French colony of Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti). There, a revolutionary army of formerly enslaved people was about to confront Napoleon’s legions and, in doing so, shatter an empire’s dream. The future of the American continent was being forged in the crucible of a slave revolt.

Napoleon’s American Dream

Across the Atlantic, the source of Jefferson’s anxiety was dreaming of empire. Napoleon Bonaparte, who had seized power in France in 1799, was a man driven by colossal ambition, and his eyes were fixed on the New World. He aimed to resurrect France’s lost North American presence and establish a self-sufficient empire that would project his power across the globe.

The glittering centerpiece of this imperial vision was the Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti). It was France’s most important holding in the Western Hemisphere - a brutal and phenomenally profitable engine of commerce. Powered by the labor of half a million enslaved people, the island produced staggering quantities of sugar, coffee, and cotton, enough to fill some 700 ships a year.

But this jewel had a fatal flaw: it was utterly dependent on outside trade for food and supplies. To solve this, Napoleon needed a secure breadbasket, and he saw it in the vast, fertile lands of the Louisiana Territory. In his grand design, Louisiana would serve as the granary for Saint-Domingue, provisioning the sugar colony and making his New World empire invulnerable to the influence of British or American trade.

To put this plan into motion, Napoleon negotiated the clandestine Treaty of San Ildefonso with Spain in 1800, forcing King Charles IV to return the immense Louisiana Territory to France. With the breadbasket secured and the jewel of the Caribbean seemingly under his thumb, Napoleon’s American dream was on the verge of becoming a terrifying reality for the United States.

The Revolt That Broke an Empire

Napoleon’s grand design, however, hinged on one critical assumption: that France could easily subdue the half-million formally enslaved people of Saint-Domingue and bend them to its will. It was a catastrophic miscalculation.

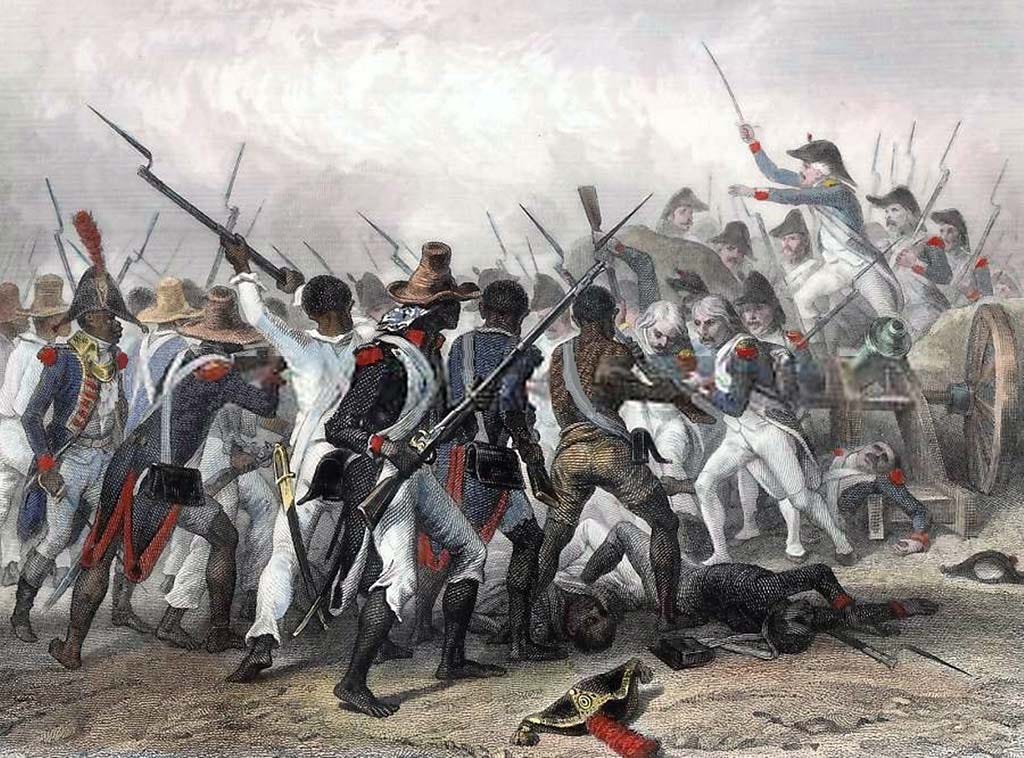

To execute the plan, he dispatched his brother-in-law, General Charles Leclerc, with a massive fleet and tens of thousands of France’s best soldiers. They arrived in early 1802 with a clear mission: depose the colony’s Black leader, Toussaint Louverture, crush his government of so-called “gilded Africans,” and formally reestablish slavery.

But Louverture and his generals, including the formidable Jean-Jacques Dessalines, met the invasion with ferocious resistance. Rather than surrender their cities, they burned them to the ground. The fighting was brutal, but the French army’s most deadly enemy was the island itself. Yellow fever tore through the European ranks, killing soldiers with horrifying speed.

The breaking point came in the summer of 1802, when news reached the island that Napoleon was officially moving to restore slavery. The rebellion exploded into a full-blown war for independence. The French found themselves in an unwinnable conflict against an enemy fighting for its very existence. “They laugh at death,” a stunned Leclerc wrote in a dispatch, realizing the futility of his mission. He himself would soon be dead from the fever.

By November 1803, the French effort had completely collapsed. Of the tens of thousands of veteran soldiers sent to the island, only about 7000 survivors were evacuated in utter defeat. On January 1, 180, Dessalines declared the independent Republic of Haiti, the first to be founded by former slaves.

For Napoleon, the loss was absolute. His New World ambitions were shattered, his treasury was drained, and the jewel of his planned empire was gone forever. The Louisiana Territory, once the strategic breadbasket, was now a massive, expensive, and completely undefendable tract of land on the far side of an ocean. And Napoleon desperately needed cash for his next war with Great Britain.

The Greatest Real Estate Panic-Sale in History

Back in Paris, the collapse of Napoleon’s colonial ambitions triggered a frantic change of plans. With his army shattered in Haiti and a new war looming against Great Britain, his need for a North American empire evaporated, replaced by an urgent and overwhelming need for cash.

This was the moment American diplomats Robert Livingston and James Monroe stepped onto the stage. Jefferson had dispatched Monroe with a clear, limited mandate: join Livingston and secure the purchase of New Orleans and, perhaps, parts of Florida. Their budget was capped at $10 million. For months, Livingston had already been in Paris, completely stonewalled by the sly French foreign minister, Talleyrand, who repeatedly denied that France even had a deal for Louisiana.

Then, on April 11, 1803, just as Monroe was arriving in the city, Talleyrand stunned Livingston with a diplomatic bombshell: What would the United States give for the whole of Louisiana? The offer was so far beyond the Americans’ instructions that it left them speechless. Napoleon, seeing the territory as a lost cause that the British would likely seize from Canada in the coming war, had decided to liquidate the asset entirely. "I renounce Louisiana," he told his finance minister. "I require a great deal of money for this war."

What followed was one of the greatest real estate fire sales in history. Recognizing this as a "fugitive occurrence" that could not be missed, Livingston and Monroe quickly entered negotiations that far exceeded their authority. They haggled with Napoleon’s finance minister, François de Barbé-Marbois, and on April 30, 1803, they struck a deal. For a final price of $15 million—about four cents an acre—the United States would acquire a territory of 827,000 square miles, nearly doubling the size of the young nation overnight.

Jefferson’s Constitutional Crisis

When news of the monumental deal reached Washington, D.C. on July 3, 1803, just in time for Independence Day celebrations, it presented President Thomas Jefferson with a profound dilemma. The man who championed a strict, literal interpretation of the U.S. Constitution now faced a situation the founding document had never anticipated. There was simply no clause that explicitly granted the president the power to purchase foreign territory and incorporate it into the Union.

The irony was immense. Jefferson, a fierce advocate for limited government, found himself in a position where he had to stretch the very limits of presidential authority to secure a deal that would forever change the nation. He was so troubled by the constitutional question that he drafted an amendment to authorize the purchase after the fact. He knew he was acting outside his enumerated powers, writing to his cabinet about the predicament: "It is the case of a guardian, investing the money of his ward in purchasing an important adjacent territory; & saying to him when of age, I did this for your good."

His cabinet, however, argued that the treaty-making power implicitly gave him the authority he needed and that waiting to pass an amendment was too risky. Napoleon’s offer was a fleeting opportunity, and the treaty had to be ratified by the end of October.

Despite fierce opposition from some Federalists, who argued, "We are to give money of which we have too little for land of which we already have too much," the deal was too good to refuse. Pressured by time and the sheer scale of the opportunity, Jefferson reluctantly set aside his constitutional scruples. He accepted his cabinet's counsel and pushed for ratification, rationalizing that the immense benefit to the nation outweighed the constitutional transgression. On October 20, the Senate agreed, ratifying the treaty by a vote of 24 to 7. The deal was done.

The Unlikely Inheritance

And so, the frantic chain of events comes to a close.

Because hundreds of thousands of enslaved people in Haiti fought for and won their freedom, Napoleon Bonaparte’s dreams of a New World empire were shattered in a fever-ridden Caribbean jungle. Because his treasury was empty and he desperately needed money to fund his impending war with Great Britain, he was forced to liquidate a continent's worth of land for pennies on the acre. And because Thomas Jefferson, a man bound by his own strict interpretation of the Constitution, was willing to bend the rules for a deal that could not be refused, the United States abruptly doubled in size.

It is a staggering sequence of cause and effect, a line of dominoes stretching from a slave revolt in the tropics to the halls of power in Paris and Washington.

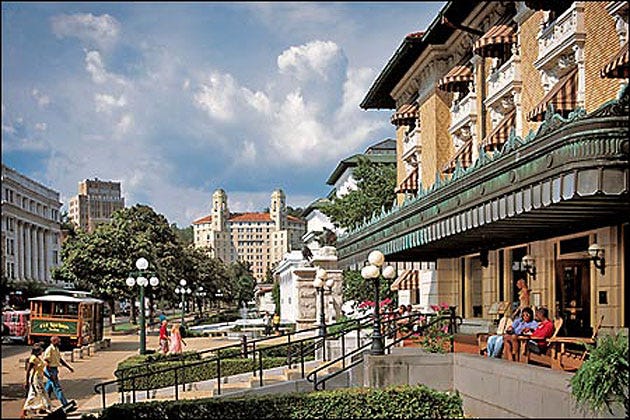

Tucked away in that vast new territory, the ancient, sacred hot springs of Arkansas—the "Valley of the Vapors"—were, almost by accident, now part of America. The first chapter of our city's American history was not written by settlers or politicians in Washington. It was written a world away, in the blood, fire, and indomitable will of a revolution that changed the map of the world.

References

Harriss, J. A. (2003, April). How the Louisiana purchase changed the world. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-the-louisiana-purchase-changed-the-world-79715124/

Jefferson, T. (1903). The Writings of Thomas Jefferson (A. A. Lipscomb & A. E. Bergh, Eds.). Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association.

Matthewson, T. (1995). Jefferson and Haiti. The Journal of Southern History, 61(2), 209–248. https://doi.org/10.2307/2211576

Muffat, S. (2022). Building Napoleon's flotillas: an invasion project fraught with difficulties. Napoleonica. The Journal, 4(4), 17–36.

Schaefer, W. G. (1995). The role of American diplomacy in the Louisiana Purchase. The History Teacher, 28(3), 347-365. https://doi.org/10.2307/494903

Thomas Jefferson's Monticello. (n.d.). Jefferson and the Louisiana Purchase. Retrieved July 9, 2024, from https://www.monticello.org/thomas-jefferson/louisiana-lewis-clark/the-louisiana-purchase/