Gunfight in Hot Springs: The Editor vs. The Mayor

When scathing editorials weren't enough, Hot Springs Mayor T.F. Linde and newspaper editor Charles Matthews settled their political feud with pistols on Valley Street. This is the wild, true story.

In the world of 19th-century politics, a war of words between a newspaper editor and a mayor was just another Tuesday. Scathing editorials were common. Pointed accusations were standard fare. But in Hot Springs, they sometimes took things a bit more personally.

On November 14, 1877, Mayor T.F. Linde decided he’d had quite enough of the ink being slung by Charles Matthews, the pugnacious editor of the Hot Springs Daily Hornet. Instead of drafting a stern rebuttal for the next edition, Linde opted for a more direct form of feedback.

He shot him. Right there on Valley Street (modern-day Central Avenue).

The brazen daytime attack wasn’t just a shocking display of violence; it was a public spectacle starring two of the city’s most combustible personalities. The mayor’s fusillade left not only the editor wounded, but also two innocent bystanders who happened to be in the line of fire. When a sitting mayor’s response to criticism is to start blasting away in the middle of town, you know you’re not in just any frontier town. And when that mayor, after being disarmed, pulls a second pistol to continue the argument? You’re in Hot Springs. This was more than a fight; it was a wild clash of ego and politics that perfectly captures the raw, stranger-than-fiction character of a city built on thermal water and hot tempers.

The Key Players: A Combustible Mix

A political feud is only as good as its combatants, and the 1877 throwdown on Valley Street was a championship bout. The men at the center of the storm weren’t just influential; they were walking powder kegs, each with a history of violence that made their eventual collision feel less like a surprise and more like an inevitability.

The Editor with a Gun: Charles Matthews

The man who provoked the mayor’s rage was Charles Matthews. He was absolutely the wrong person to pick a fight with. An Englishman by birth, Matthews had landed in Austin, Texas, working as a bartender. It was there, on Christmas Day of 1876, that he got a real-world education in frontier justice.

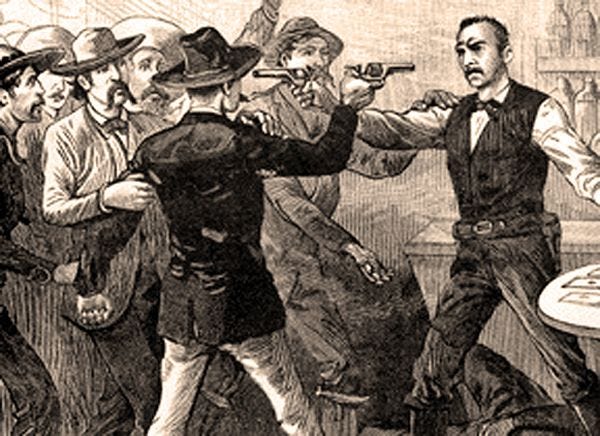

The story is pure pulp. Matthews’s boss, Mark Wilson, gets into an argument with the infamous gunfighter Ben Thompson. Wilson calls Thompson a liar - a fatal error - and gets slapped. Wilson’s response? He grabs a shotgun and fires. He misses. Thompson didn’t. He drew his Colt .45 and killed Wilson on the spot. Seeing this, our man Charles Matthews grabs a rifle from under the counter and takes a shot at one of the deadliest men in Texas. He only managed to graze him. Thompson, a man not known for his patience, turned and fired his last round, tearing through Matthews’s neck and mouth. He was left for dead.

But he didn’t die.

He arrived in Hot Springs in early 1877 with a nasty scar and absolutely zero fear of confrontation. He took a respectable job writing for the Hot Springs Sentinel, but the polite constraints of working for someone else clearly didn’t suit him. In a move that was pure Matthews, he bought the failing Hot Springs Daily Hornet and immediately turned his stinger on the city’s powerful elite. He had survived a bullet to the face; he wasn’t about to be intimidated by a mere mayor.

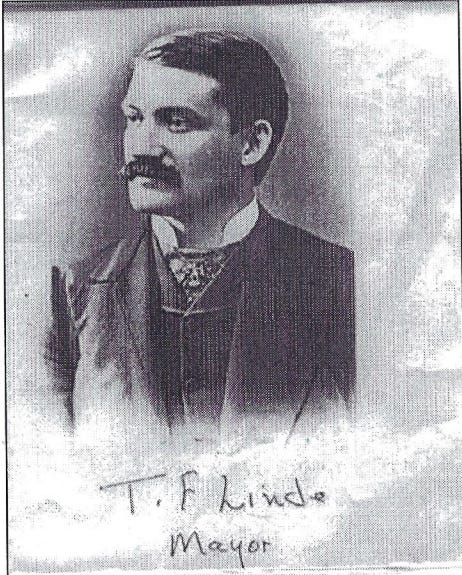

The Fighting Dentist: Mayor T.F. Linde

The man holding the mayor’s office - and two pistols apparently - was Theodore F. Linde. To call him simply “the mayor” or “a dentist” is to do the man a profound disservice. His life before ever setting foot in Hot Springs reads like a dime novel, and it explains a whole lot about why he thought a shootout was a perfectly reasonable way to handle bad press.

Born in Memphis, Linde was the son of a successful gunsmith, so you could say he was practically born into the business of firearms. He didn’t wait long to get into a real fight, either. At the tender age of fifteen, he joined the Confederate army, serving under a “who’s who” of legendary generals: P.T. Beauregard, Albert Sidney Johnston, and the formidable Nathan Bedford Forrest. The war ended, but Linde’s taste for adventure didn’t. He studied dentistry and, in a move that suggests he wasn’t planning on a quiet life, opened a practice in Brazil.

When that didn’t pan out, he drifted back to the States. He landed in Bryan, Texas, where he promptly got into a duel, disarmed his opponent, and magnanimously let the man live. You can’t make this stuff up. By the time he arrived in Hot Springs in 1873, he was a seasoned, worldly man with a well-established temper.

He was also a fascinating political contradiction. He earned immense loyalty from the city’s poor by strong-arming the big hotels into donating their unused food to the indigent. Yet, this was the same man who, as both mayor and the presiding Police Judge, held the power to fine a man for spitting on the sidewalk one minute, and then pull a gun on another the next. He was a benevolent leader with a hair-trigger temper - the perfect combustible ingredient for a town like Hot Springs, and the perfect target for an editor like Charles Matthews.

The Powder Keg: Politics and Printer’s Ink

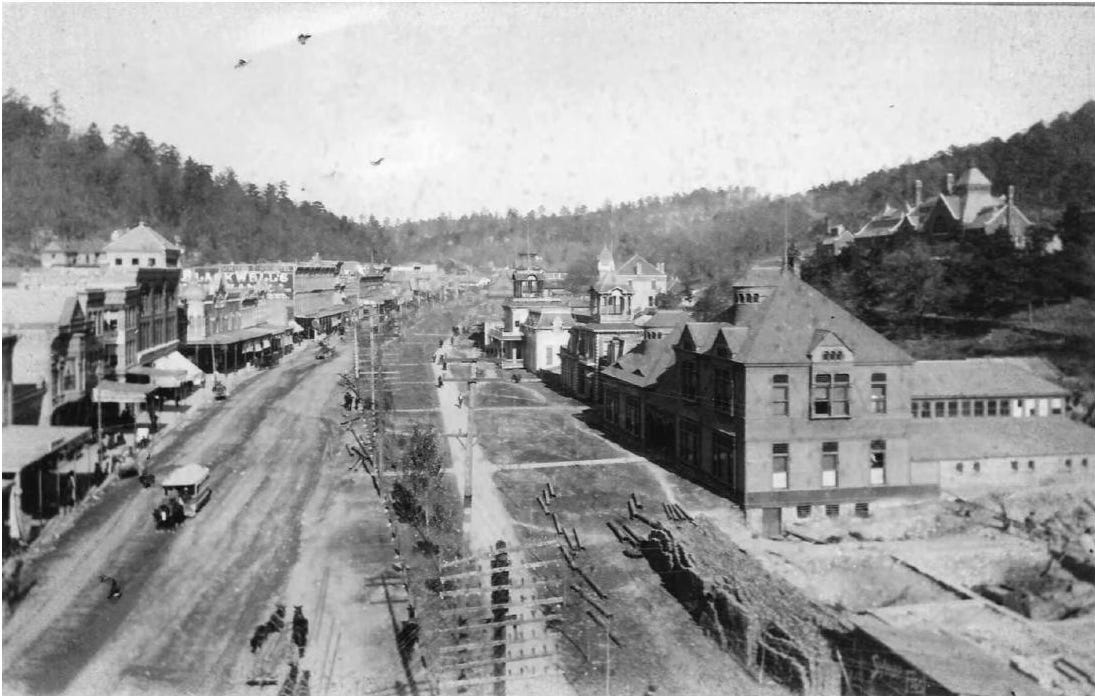

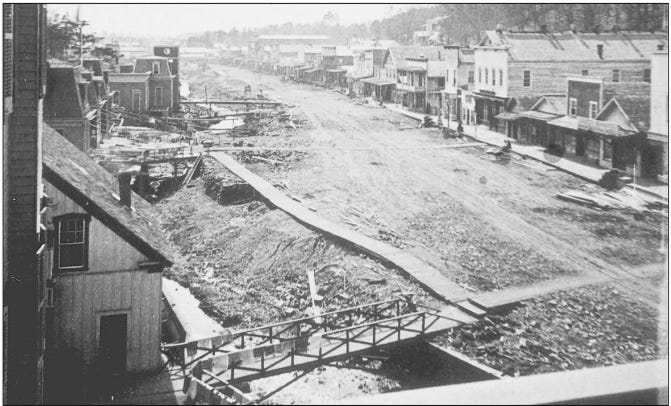

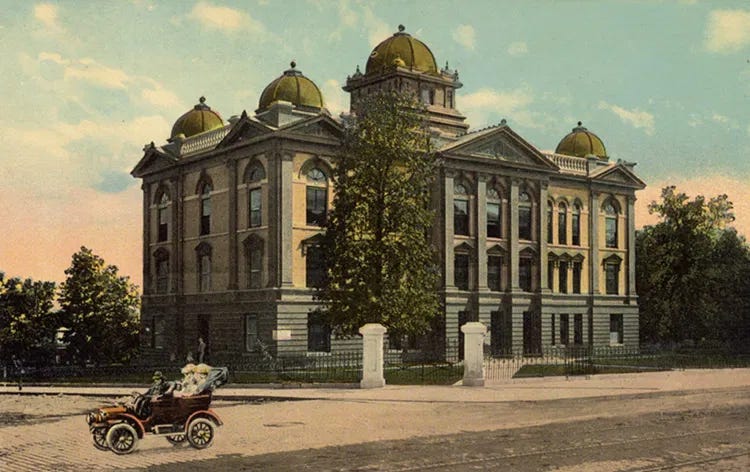

Hot Springs in the 1870s wasn’t for the faint of heart. Forget the serene, healing resort you might imagine. This was a raw, frontier town with a saloon on every corner and a pistol on every hip. One early visitor, probably after a long walk down Valley Street, wrote home that he believed “every other business is a saloon.” He wasn’t far off. The main drag boasted at least eighteen official watering holes, and that didn’t even count the liquor sold in restaurants, billiard parlors, and cigar shops.

It was a place where politics was a full-contact sport, and disagreements were often settled with a fast draw. The town had the feel of Dodge City or Tombstone, with wooden plank sidewalks, hitching rails, and a constant, simmering tension. Every single mayoral election was hotly contested, usually with the town’s powerful gambling interests pulling strings behind the scenes.

Into this simmering pot of booze, politics, and gunpowder stepped Charles Matthews, armed with his newspaper and a formidable grudge. From the moment he took over the Hornet, he aimed its “stinger” squarely at Mayor Linde’s administration. Matthews saw a glaring hypocrisy in the way the city was run, and he wasn’t the kind of man to keep quiet about it. Week after week, he blasted Linde in print, accusing him of being tough on the little guy while letting the big fish swim free. The mayor’s court, Matthews claimed, was quick to fine working folks for minor infractions like spitting on the sidewalk or missing their annual day of forced labor on the city’s streets. Meanwhile, the powerful and profitable gambling dens operated with a wink and a nod from city hall.

This wasn’t just criticism. In a town like Hot Springs, it was a public challenge and an attack on the mayor’s authority and his honor. And it was only a matter of time before the powder keg ignited.

The Flashpoint: Gunsmoke on Valley Street

The war of words finally became a war of lead on November 14, 1877. When Mayor Linde spotted Charles Matthews on the muddy thoroughfare on Valley Street, there was no formal challenge, no ten paces at dawn. There was just pure, unadulterated rage.

Linde, absolutely furious, confronted his tormentor. Without a word, he reached into his coat, pulled a pistol, and simply started firing. The surprised Matthews was hit almost immediately, taking a bullet to the wrist and a graze to the chin. But remember, this was a man who had already survived a gunfight with Ben Thompson. Bleeding and stunned, he somehow managed to lunge at the mayor, grab the pistol, and wrestle it away from him.

For most street brawls, that would be the end of it. A sensible person might call it a day.

But T.F. Linde wasn’t most men, and he had apparently come prepared for a protracted argument. Undaunted, the mayor of Hot Springs reached into his coat and pulled out a second pistol. You have to admire the preparation, if not the policy. He resumed firing, this time hitting Matthews with a much more serious wound to the chest.

The editor staggered back, trying to retreat. But Linde, completely consumed by his fury, just kept shooting. His wild shots flew down the street, hitting a poor street peddler and a city alderman who had the terrible timing to step out of his store to see what all the noise was about. In a matter of minutes, the mayor of Hot Springs had shot three people in the middle of his own town. The only question left was, what on earth happens now?

The Aftermath: No Charges, New Friends

What happens when the mayor of your town shoots three people on the main street in broad daylight? In any normal city, you’d expect a swift arrest, a scandalous trial, and a new mayor.

But Hot Springs has never been a normal city.

You’d think the local constabulary would have a few questions for a man who just emptied two pistols in public, wounding three citizens. You’d be wrong. After the smoke cleared, the most incredible part of the story unfolded: absolutely nothing happened. A deep dive into the city’s arrest, jail, and court records from the period reveals a stunning void. There’s not a single, solitary entry indicating that Mayor T.F. Linde was ever charged, fined, or even officially questioned for the brazen public assault. He just went back to being the mayor.

Meanwhile, what about our editor, Charles Matthews? The man was left bleeding in the street from a serious chest wound? He just… got better. Again. For the second time in as many years, he recovered from his injuries that would have killed most men, apparently fueled by sheer stubbornness. He got back on his feet and went right back to work at the Hornet.

And this is where the story takes a final turn into the truly bizarre, the kind of twist that makes you wonder if something was in the thermal water. After nearly killing each other in a public gun battle, Charles Matthews and T.F. Linde became friends. It’s a fact so strange it feels like a misprint in the historical record, but it’s true. The feud was over. Presumably, they agreed to settle future disagreements with less ammunition.

A Different Kind of Hot Springs Cure

When the gunsmoke finally cleared over Valley Street, it revealed one of the most perfectly “Hot Springs” stories ever told. It’s a tale that perfectly captures a time when personal honor, political power, and public criticism collided in a hail of bullets - and nobody even got arrested.

This wasn’t just a simple street fight; it was a bizarre chapter in the city’s history that speaks volumes about its character. You have a mayor who solves political problems with a backup pistol, an editor who survives being shot in the face for the second time, and a town where the whole affair results not in a trial, but a handshake. It proves that for some of the city’s founders, the ultimate cure for a political headache wasn’t found in the thermal waters, but in the barrel of a gun. And sometimes, apparently, it even led to a beautiful friendship.

If you enjoyed this dive into the wild side of Hot Springs history, don't keep it to yourself! Share it with a friend who appreciates a good stranger-than-fiction tale.

And for more stories that you won't find in the official tour guides, upgrade to a paid subscription. You'll get access to exclusive content, bonus materials, and you can join the conversation in the comments. I'd love to know—what did you think of the fighting dentist?

References

Allbritton, O. E. (2006). Hot Springs gunsmoke. Garland County Historical Society.

Allsopp, F. W. (1922). History of the Arkansas press for a hundred years and more. Parke-Harper Publishing Co.

Arkansas Gazette. (1877, April). Our mayoralty ticket.

Arkansas Gazette. (1877, November 16). A bloody affray.

Austin American-Statesman. (1876, December 28). Personal.

Benson, F. M., & Libbey, D. S. (n.d.). History of Hot Springs National Park. Southwest Regional Office, National Park Service.

Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. (n.d.). Digital collections.

The Daily Sentinel. (1877, November 21). The Linde-Matthews shooting affair.

The Daily Sentinel. (1878, January 10). Local matters.

The Encyclopedia of the new west. (1881). The United States Biographical Publishing Company.

Hanley, R. (2011). A place apart: A pictorial history of Hot Springs, Arkansas. University of Arkansas Press.

Hanley, R., & Hanley, S. (2000). Hot springs, Arkansas (Images of America). Arcadia Publishing.

Hot Springs City Directories (1870s-1880s). Digital Collections, Garland County Library.

Hot Springs Guest Guide. (2020, February 17). The history of Hot springs.

Hot Springs Telegraph. (1877, November). City council proceedings.

Maillard, K. (2011). Hot Springs, Arkansas. Southern Cultures, 17(3), 90-110.

Miller, R. H. (1969). The legal fraternity and the making of a new state constitution: Arkansas, 1874. The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 28(2), 127–142.

Moneyhon, C. H. (1997). The impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction on Arkansas: Persistence in the midst of ruin. University of Arkansas Press.

The Record: Garland County Historical Society Yearbook. (Various years).

Rickard, J. K. (2009). For 'the good of the people': The populist press in Arkansas. The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 68(1), 27-46.

Schoenberger, D. T. (1993, January). Charles Matthews, editor with a gun. True West Magazine.

Shugart, S., Hill, T., et al. (2024). When did it happen? A chronology of historic events at Hot Springs National Park. National Park Service.

Williams, C. F. (Ed.). (1991). A documentary history of Arkansas. University of Arkansas Press.