A Town Abandoned: The True Story of Hot Springs During the Civil War

Forget the myths of grand battles. Discover the forgotten history of how a fledgling spa town became a temporary state capital, only to be consumed by a brutal guerrilla war.

Sure, Hot Springs was the state capital for a minute. It’s a go-to bit of Civil War trivia for this town - the story of a panicked governor, a stash of state records, and a hasty retreat to the safety of the Quachitas. It’s a quirky, almost comical, image. And once Governor Rector packed his wagons and scurried back to Little Rock a few weeks later, it’s tempting to think that was the end of the town’s role in the great conflict.

But it wasn’t. Not even close.

That strange little chapter as a temporary capital isn’t the real story of Hot Springs during the war. It’s just the prologue. The real story, the one that got buried under the floorboards of history, is what happened the moment the government fled for the second time. When the officials left, the armies followed, creating a power vacuum in these mountains that was filled by something far more terrifying than any invading force. The war that descended upon this valley wasn’t a formal conflict of blue and gray. It was a brutal, intimate war of ambush and reprisal, fought by pro-Confederate bushwhackers and pro-Union “Mountain Feds” who used the chaos to settle scores and terrorize their neighbors. The temporary capital was a historical curiosity; the guerrilla war it left in its wake was the reality that almost erased this town from the map.

The Anomaly in the Ouachitas

Forget what you know about the antebellum South. Hot Springs has never played by the rules, and on the eve of the Civil War, it was an absolute anomaly. It wasn’t a plantation town; it was a frontier spa, a place built on the unique business of health and hospitality. While the rest of Arkansas was passing increasingly vicious laws to expel its tiny free Black population, Hot Springs was quietly becoming a haven. The town’s lifeblood wasn’t cotton; it was the steady stream of wealthy, ailing visitors who needed lodging, food, and guides.

This created a social structure found nowhere else in the state. Alongside the roughly 65 enslaved individuals working in the hotels, a significant and vital community of free people of color carved out a life here. They worked as blacksmiths, musicians, bath attendants, and guides—skilled labor essential to the town’s function. This all took place in the strange legal twilight of the federal reservation (land that would later become the heart of Garland County). With the government in DC paying no attention, a unique three-tiered society of white residents, enslaved laborers, and free Black entrepreneurs coexisted in a delicate, complicated balance. It was a world away from the rigid doctrines of the cotton kingdom, a precarious and utterly unique culture that the coming war would shatter into a thousand pieces.

The Capital in the Woods: Governor Rector’s Hasty Retreat

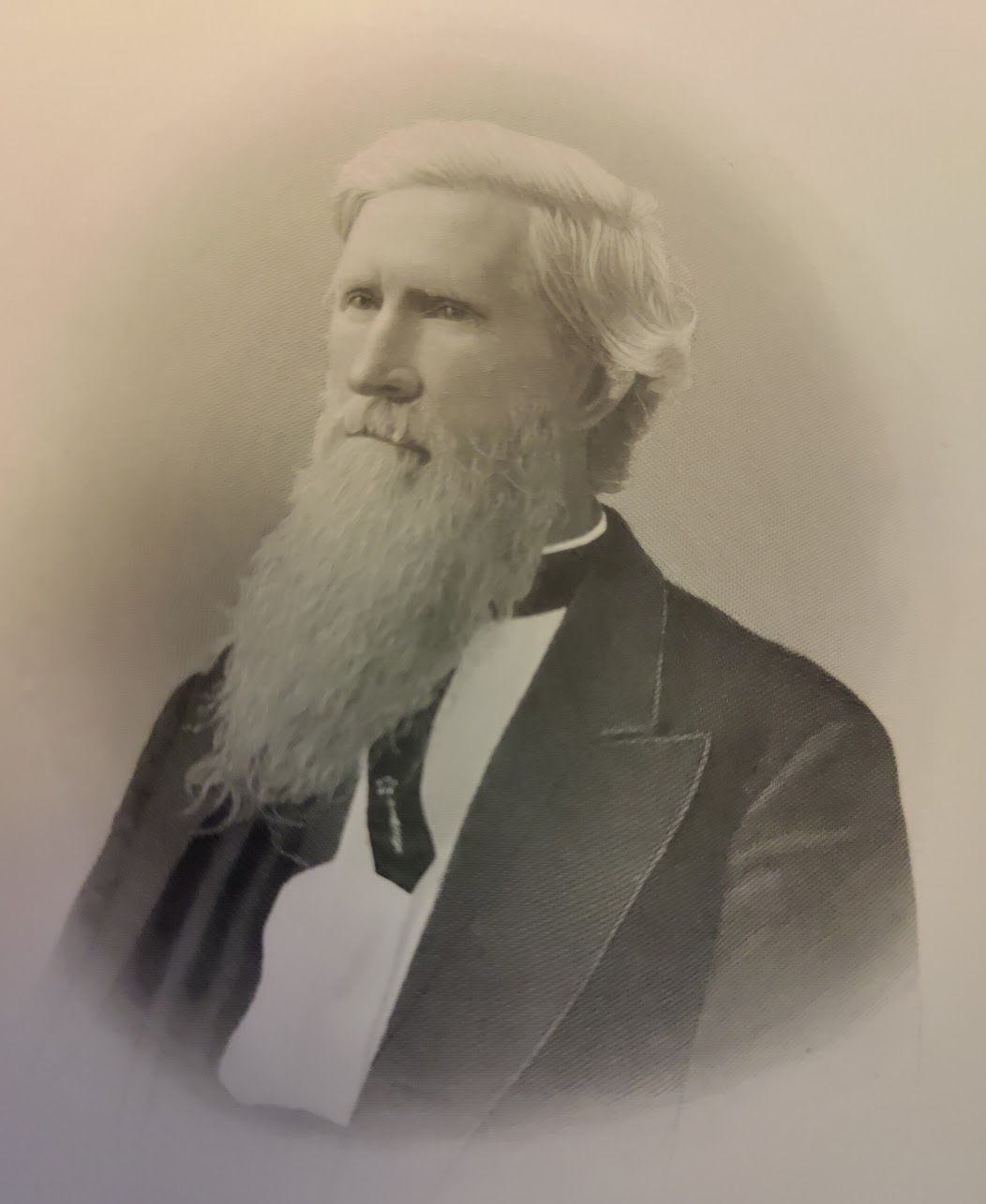

By the spring of 1862, the Confederate war effort in Arkansas was in shambles. After a stinging defeat at Pea Ridge, Union forces under General Samuel Curtis were pushing south, and it looked for all the world like Little Rock was their next target. Governor Henry M. Rector, a man whose political instincts often defaulted to self-preservation, decided it was time to get out of Dodge. On his authority, and to the complete surprise of many, he ordered the state archives and treasury loaded onto wagons and fled to the only place he trusted: his personal property in Hot Springs.

The new Confederate “capital” was little more than Rector’s modest summer cottage, with his nearby frame bathhouse and log kitchen serving as the state’s administrative hub. His tenure here, from May 6th to July 14th, was less a functioning government and more a masterclass in paranoia and futility. While he issued a few fiery proclamations from the woods, calling for guerrilla warfare and attempting to rally the state, his main accomplishment was creating a political firestorm. His flight was widely regarded as an act of cowardice and incompetence, earning him the scorn of both military leaders and the public. They saw a governor hiding out in a spa town while the rest of the state was left to fend for itself.

And the ultimate irony? Rector’s entire government-in-exile was squatting on the Federal Reservation - enemy territory. The heart of Confederate Arkansas was beating on a patch of land owned by the United States. When Union forces eventually shifted their focus away from Little Rock, Rector, facing immense political pressure and ridicule, sheepishly packed his wagons and moved the capital back. He had succeeded only in destabilizing his government and, more importantly for Hot Springs, creating the power vacuum that would unleash the real war upon the town.

The No-Man’s-Land: The Peak of Anarchy

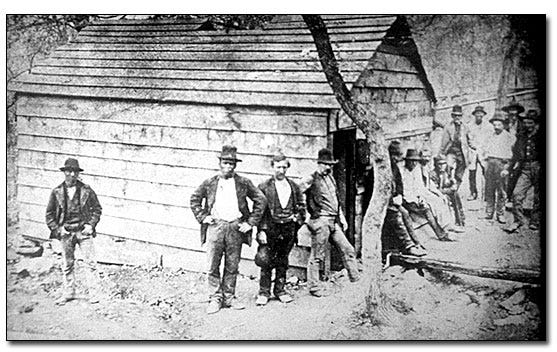

When Governor Rector fled back to Little Rock, he took the last semblance of official order with him. His retreat, combined with the Confederate high command pulling most regular troops east to the Mississippi, created a power vacuum that turned Hot Springs into a lawless hellscape. This wasn’t a war of neat battle lines; it was a chaotic, personal conflict. As one Union cavalryman bluntly wrote of his time in the area, he intended to “subsist… on the country,” taking horses, mules, and supplies, but being “careful to see that secessionists supplied me with these wants.” It was a policy of legalized plunder that erased any distinction between soldier and civilian.

The void was filled by pro-Confederate “bushwackers” and their Unionist counterparts, the “Mountain Feds.” These weren’t just soldiers; they were neighbors using the war as a license to settle old scores. The violence was constant and brutal. Federal troops swept through in 1864, arresting any Hot Springs resident who refused to take a loyalty oath, further terrorizing a population caught in the crossfire. The most well-documented event happened in the summer heat of July 1864. A scouting battalion from the 4th Arkansas Cavalry (US) rode into town, only to be ambushed by Confederate guerrillas right on what is now Central Avenue.

The fighting then spilled out to a place called Farr’s Mill, where Gulpha Creek meets the Ouachita River. There, Confederate companies under the command of men named Cook and Crawford slammed into the Union cavalry. When the smoke cleared, the Confederates had lost four men and six were wounded; the Union expedition suffered twelve casualties in total. This wasn’t a grand, strategic battle; it was a vicious, bloody street fight and a roadside ambush. It was the perfect microcosm of the war in Hot Springs: personal, deadly, and fought not for territory, but for survival and revenge in the ruins of a once-thriving town.

The Later Years & Lasting Legacy

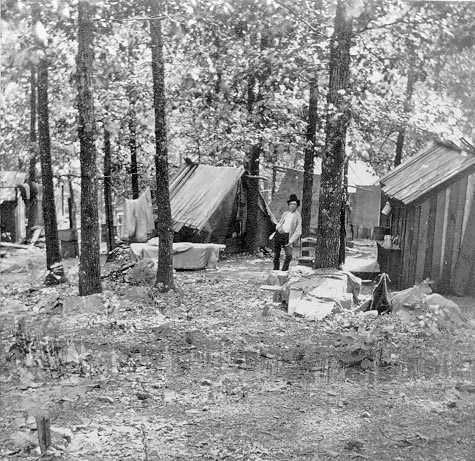

When the guns finally fell silent in 1865, Hot Springs was a ghost of its former self. The guerrilla war had done its work. Most of the town had been put to the torch, leaving behind a grim collection of charred ruins and a handful of buildings that had somehow survived the anarchy. The vibrant, contradictory community that had existed before the war was gone, its residents either dead or having fled to Texas or Louisiana with no intention of returning. The place was, for all intents and purposes, a town-sized scar on the landscape.

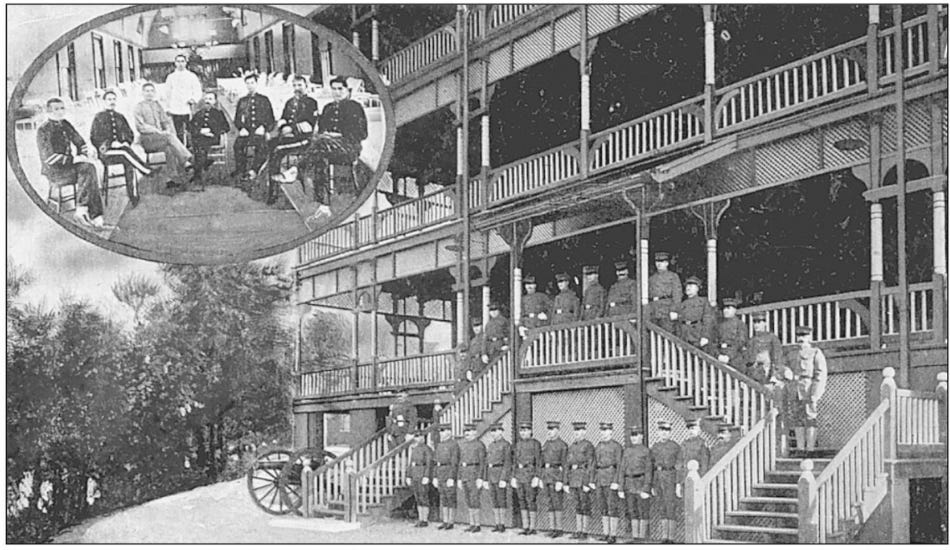

But the waters still flowed. And as the country began to bind its wounds, a new kind of visitor started trickling back into the valley: veterans. They came from both sides of the conflict - men who had worn the blue and the gray - all seeking relief from the lingering pain of their injuries in the one place they’d heard might offer a cure. They bathed in crude, dugout pools on the hillside, a far cry from the resort’s antebellum comforts. This slow, steady influx of broken soldiers forged the true legacy of the war in Hot Springs. It transformed the town’s reputation from a place of leisure to a place of desperate healing.

And it’s here, in the shared misery of these former enemies, that the old myth of the Civil War hospital town finds its ironic postscript. There was no grand hospital during the war, but the suffering created by the war is what ultimately led to one. The sight of so many veterans seeking solace in the thermal waters eventually sparked the idea for the Army-Navy Hospital, which opened its doors in 1887. The legend got the timing wrong, but it stumbled upon the emotional truth: the Civil War is what cemented Hot Springs as a place of recovery, not by the design of generals, but through the quiet pilgrimage of the wounded.

Why This Forgotten History Matters

So why rake up these old ghosts? Because the story of the temporary capital, as quirky as it is, has overshadowed the much more important story of what came after. The true trial by fire for Hot Springs wasn’t hosting a panicked governor for a few weeks; it was surviving the years of brutal, neighbor-on-neighbor violence that followed. The town’s near-total destruction and its subsequent rebirth, fueled by the very veterans who had fought the war, is the real crucible that forged the city’s modern identity.

This forgotten chapter is essential to understanding the stubborn, slightly strange resilience of Hot Springs. It’s a place that has always existed on its own terms, a town that was nearly wiped off the map and then rebuilt itself into a national icon, not on a foundation of grand strategy, but on the quiet, desperate hope for healing. The real history is always messier, bloodier, and far more fascinating than the neat stories we tell ourselves.

If you found this deep dive into our town's hidden history compelling, please consider sharing it with someone who needs to know the real story.

For more exclusive articles and access to primary source documents from the archives, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Your support makes this research possible.

References

Allbritton, O. E. (n.d.). Hot Springs Gunsmoke. Garland County Historical Society.

Arkansas State Archives. (n.d.). 1864 April 01: The Bumble Bee Newspaper. Arkansas Digital Archives. Retrieved August 17, 2025, from https://ar-digital.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/smcs/id/282/

Bailey, A. J., & Sutherland, D. E. (2007). Civil War Arkansas: Beyond Battles and Leaders. University of Arkansas Press.

Benson, F. M., & Libbey, D. S. (n.d.). History of Hot Springs National Park. National Park Service.

Christ, M. K. (2010). “The patience of Job”: The Drennen-Scott letters, 1862-1865. The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 69(3), 254–268.

Christ, M. K. (2012). “This Day We Begin a New and More Perilous Life”: The 1863-1865 Diary of Captain Allen W. Bishop, 1st Arkansas Cavalry (U.S.). The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 71(4), 405–424.

Christ, M. K. (2013). “We are in for it now”: The 1862-1863 Diary of a Union cavalryman. The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 72(4), 362–383.

Christ, M. K., & Lause, M. A. (2011). The Civil War in Arkansas: A companion. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies.

DeBlack, T. A. (1994). With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861-1874. University of Arkansas Press.

Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (n.d.). African Americans. Retrieved August 17, 2025, from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/african-americans-407/

Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (n.d.). Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874. Retrieved August 17, 2025, from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/civil-war-through-reconstruction-1861-through-1874-388/

Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (n.d.). Garland County. Retrieved August 17, 2025, from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/garland-county-770/

Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (n.d.). Jayhawkers and Bushwhackers. Retrieved August 17, 2025, from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/jayhawkers-and-bushwhackers-2280/

Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (n.d.). Newspapers during the Civil War. Retrieved August 17, 2025, from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/newspapers-during-the-civil-war-7896/

Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (n.d.). Slavery. Retrieved August 17, 2025, from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/slavery-1275/

FamilySearch. (n.d.). Garland County, Arkansas Genealogy. FamilySearch Wiki. Retrieved August 17, 2025, from https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Garland_County,_Arkansas_Genealogy

Hanley, R. (2011). A Place Apart: A Pictorial History of Hot Springs, Arkansas. University of Arkansas Press.

Hanley, R., & Hanley, S. (n.d.). Hot Springs, Arkansas (Images of America). Arcadia Publishing.

Historical Marker Database. (n.d.). Skirmish at Farr's Mill. Retrieved August 17, 2025, from https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=170440

Historical Marker Database. (n.d.). State Capitol Moves to Hot Springs. Retrieved August 17, 2025, from https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=211077

Lankford, G. E. (2006). Bearing Witness: Memories of Arkansas Slavery: Narratives from the 1930s WPA Collections. University of Arkansas Press.

Moneyhon, C. H. (1994). The Impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction on Arkansas: Persistence in the Midst of Ruin. University of Arkansas Press.

National Archives. (n.d.). Civil War Records. Retrieved August 17, 2025, from https://www.archives.gov/research/military/civil-war

National Park Service. (2021, May 21). Civil War Connections at Hot Springs National Park. U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved August 17, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/civil-war-connections-at-hot-springs-national-park.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.). Arkansas Civil War Battles. Retrieved August 17, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/arkansas.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.). When Did It Happen? A Chronology of Historic Events at Hot Springs National Park.

Paige, J. C., & Harrison, L. S. (1988). Out of the Vapors: A Social and Architectural History of Bathhouse Row. U.S. Department of the Interior / National Park Service.

Roberts Library. (n.d.). A Nation Divided: Arkansas in the Civil War. Retrieved August 17, 2025, from https://robertslibrary.org/collection/civil-war/home/

Sifakis, S. (1988). Compendium of the Confederate Armies: Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, and the Confederate Units and the Indian Units. Facts on File.

Sutherland, D. E. (1999). A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War. The University of North Carolina Press.

Sutherland, D. E. (2009). Guerrillas, Unionists, and Violence on the Confederate Home Front. University of Arkansas Press.

UA Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture. (n.d.). A Nation Divided: Arkansas in the Civil War -- Manuscript Collections. Retrieved August 17, 2025, from http://bc-digital.org/civilwararkansas/manuscript-collections.html

Warner, E. J. (1959). Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Louisiana State University Press.

Warner, E. J. (1964). Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Louisiana State University Press.

Wood, W. D. (1903). Reminiscences of reconstruction in Arkansas. Arkansas Historical Association.

Woods, J. M. (2009). Rebellion and Realignment: Arkansas's Road to Secession. University of Arkansas Press.

Wooster, R. (1993). Civil War Generals of the Confederacy: A Sesquicentennial study. University of Nebraska Press.